Gadsden’s Wharf, on the Cooper River waterfront at the eastern edge of Charleston, South Carolina, was once the largest landing site for slave ships carrying their human cargo to the United States. About 100,000 Africans embarked there during the height of the transatlantic slave trade in the early 1800s, so many that an estimated 90 percent of African Americans can trace at least one ancestor to Charleston.

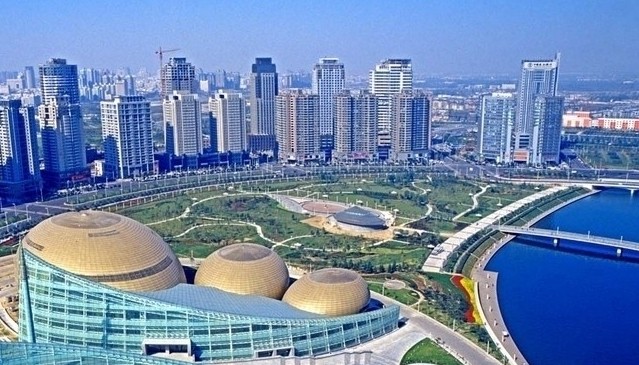

Today, the wharf is the site of the International African American Museum, a haunting 150,000-square foot facility that tells the sobering story of American slavery through words, photos, films, artifacts and artworks.

The 426-foot long, one-story building is raised above ground by 13-foot pillars covered with tabby, concrete made from a mixture that includes crushed oyster shells. On the pavement below are the engraved outlines of human bodies, periodically washed over by water from a shallow pool, representing all the shackled slaves packed into ships where thousands died from malnutrition, disease and beatings while crossing the ocean.

The museum, which opened last year, traces the history of the African American experience from slavery to the election of the first black U.S. president. It includes exhibits on Charleston’s major role in the slave trade, the abolitionist movement, the Jim Crow era, and the civil rights protests of the 1950s and ’60s. It also has a public research center where African Americans can try to trace their family roots, a task that is often extremely difficult due to the haphazard recordkeeping of many slaveholders.

The museum was one of the highlights of a recent, five-day trip my wife Pat and I made to Charleston, where we hooked up with old friends who were visiting from Nashville. I hadn’t been in Charleston for almost 20 years, though I spent considerable time there when I was a young reporter in Greenville, South Carolina, back in the late 1970s.

The Charleston metro population has more than doubled since then to about 800,000, and the area is dealing with many of the problems faced by other fast-growing regions such as traffic jams, expensive housing and suburban sprawl. Nevertheless, the city has managed to retain its Southern charm and colonial architecture while offering a lively arts and entertainment scene.

It’s also an education center that’s home to three universities — the College of Charleston, the Medical University of South Carolina and The Citadel, a state military school whose alumni include author Pat Conroy (“The Prince of Tides,’’ “The Great Santini”), former NFL star Stump Mitchell and wacky right-wing congresswoman Nancy Mace, whose claim to fame is wearing skin-tight outfits to work on Capitol Hill.

The College of Charleston has one of the prettiest city campuses in the country. Walkways are lined with giant oak trees, spacious courtyards brim with flowers, and academic departments are housed in stately antebellum homes. One of the popular student hangouts is Caviar & Bananas, a gourmet cafe where we stopped for lunch and single-handedly doubled the average customer age.

Charleston is nicknamed the Holy City because it has more than 400 churches of various denominations, and the city skyline is dotted with steeples. They include the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the oldest black churches in the South and the site of a notorious massacre in 2015 when nine people were killed during a Bible study by a 21-year-old white supremacist. (On the waterfront one day, a man walking his dog told us that the mutt’s original owner was one of those murdered at the church.)

One of the most photographed spots in Charleston is Rainbow Row, 13 brightly colored, 18th-century homes that wouldn’t seem out of place in Disneyland. The neighborhood had become run-down by the end of the Civil War and a revival didn’t start until the 1930s, when a local couple bought a block of homes and painted them pink in a tribute to the Caribbean heritage of the merchants who settled the area. Other neighbors followed suit, using similar pastel colors, and eventually it became known as Rainbow Row.

Another Charleston landmark is Fort Sumter, built on an artificial island to protect the East Coast from a naval invasion. It was here that the Civil War started on April 12, 1861, when the South Carolina militia (the state had seceded from the Union almost four months earlier) fired on the federal garrison and captured the fort the following day.

There isn’t much left of the original fort, which was reduced to rubble during an unsuccessful Union attempt to retake it in 1863. Much of the island is now covered by Battery Huger, an ugly black concrete structure built in 1898-99 in response to the Spanish-American War.

During a flag lowering and folding ceremony during our visit, I learned that the U.S. went through four different flags during the Civil War, ranging from 33 stars to 36 stars. (The increase reflected the addition of three states — Kansas, West Virginia and Nevada.) Although the Confederacy had its own flags, the stars on the U.S. flag continued to reflect the 11 states that seceded from the Union. (I saw a few Confederate flags flying in Charleston, but mercifully none at Fort Sumter.)

Another popular tourist site is the City Market, an arts and crafts complex that stretches four blocks from the historic Market Hall building. Vendors sell everything from hand-woven sweetgrass baskets and beaded jewelry to homemade jerky and landscape photos.

I stopped to talk with David Mosho, the proprietor of Bubba MoSho jerky, which comes in flavors ranging from Pineapple Heat Teriyaki to Butter Garlic. David learned how to make the dried beef strips from his dad George, an engineer and retired Marine who made the stuff as a hobby. “I got the secret recipe and I ain’t giving it away,’’ David grinned.

One day we drove out to Sullivan’s Island and the Isle of Palms, a pair of slender barrier islands connected by a short bridge. These are wealthy enclaves with large beachfront homes, pristine parks and award-winning golf courses. We ate lunch on the Isle of Palms at Acme Lowcountry Kitchen, a no-frills eatery where I had shrimp and grits that a local friend bills as the “best in the world.’’

Charleston is foodie heaven, whether you favor fancy or down-home cuisine. The most unusual place we ate was Church and Union, located in a century-old red brick church where the vaulted ceiling is hand painted with the text of Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War.’’

I don’t know if Sun Tzu had anything to say about fried chicken, but mine was delicious.

What a fascinating report on Charleston. Though I’ve been there, and more than once, you saw the most! I did however miss pictures of you and Pat.

Yes, balmy Charleston. I believe the museum was not there when we were there last; it sounds worthy of a return visit.

I’m not a Civil War buff and wouldn’t ordinarily read or recommend a book on the subject but I enjoyed reading Erik Larson’s, “The Demon of Unrest,” published this year. It provides a play-by-play account of the events leading up to the Civil War.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/195608683-the-demon-of-unrest