Most iPhones are made in China, including more than a million a week at a huge Foxconn plant in Zhengzhou, so why are they more expensive here than in the U.S.?

The answer, according to the New York Times, is twofold. First, Chinese mobile companies don’t discount the cost of the phone the way U.S. carriers do when you sign a contract. Also, unlike iPhone buyers in the U.S., those in China must pay a 17 percent value-added tax.

When the latest iPhone models were released in September, the starting price for an unsubsidized 5S in China was $864, a third more than the $650 cost of the same phone in the U.S. The cheaper, plastic-covered 5C cost $733 here without a contract discount, putting it out of reach for the vast majority of Chinese workers.

However, the cost may drop dramatically if Apple reaches an agreement with China Mobile, the country’s largest cellphone carrier. The two sides seem to be moving closer to a deal, which might persuade Apple to drop the price of iPhones here in order to attract some of China Mobile’s 700 million customers.

By the way, I’ve been using my year-old iPhone 5 in Zhengzhou without too many problems. I can’t get voicemail or 4G speed from my carrier (China Unicom), but the overall service is decent. My biggest headaches have been caused by updating to iOS 7, including the loss of sound on ringtones and message alerts.

Getting iPhone support is difficult in China. While there are official Apple stores in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, Zhengzhou doesn’t have one. (You can find plenty of fake ones, though.) So my only option for English-language support is calling the U.S. number on Skype and hoping my lousy Internet connection doesn’t cut me off while I’m waiting for a customer representative.

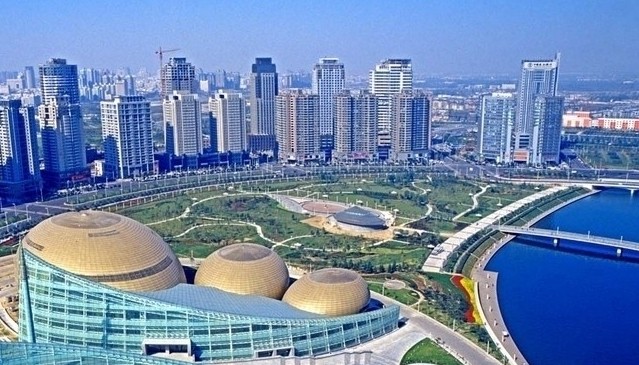

One more Foxconn note: The plant on the outskirts of Zhengzhou makes more iPhones than any other place in the world. At peak production times, it employs 300,000 workers and cranks out 200,000 iPhones a day. This high-speed assembly line comes at a price. The harsh conditions – according to various reports, workers sometimes go three months without a day off and live in prison cell-like dorm rooms crammed with as many as eight people — have reportedly led to several suicides and a brief work stoppage.

I hope to visit the plant while I’m here, though I doubt I’ll be welcome if they find out I’m a former journalist.

Rick,

Is it really that important to visit the plant? I hear the great wall is nice this time of year.