Ask the average American about Nova Scotia and they’ll probably draw a blank. If they know anything at all, it’s probably because they’ve eaten lox or lobster from the eastern Canadian province.

So here’s a short primer on Nova Scotia, where my wife and I recently spent a memorable week that included more than 1,000 miles of driving, two hospital visits and the best seafood chowder I’ve ever eaten.

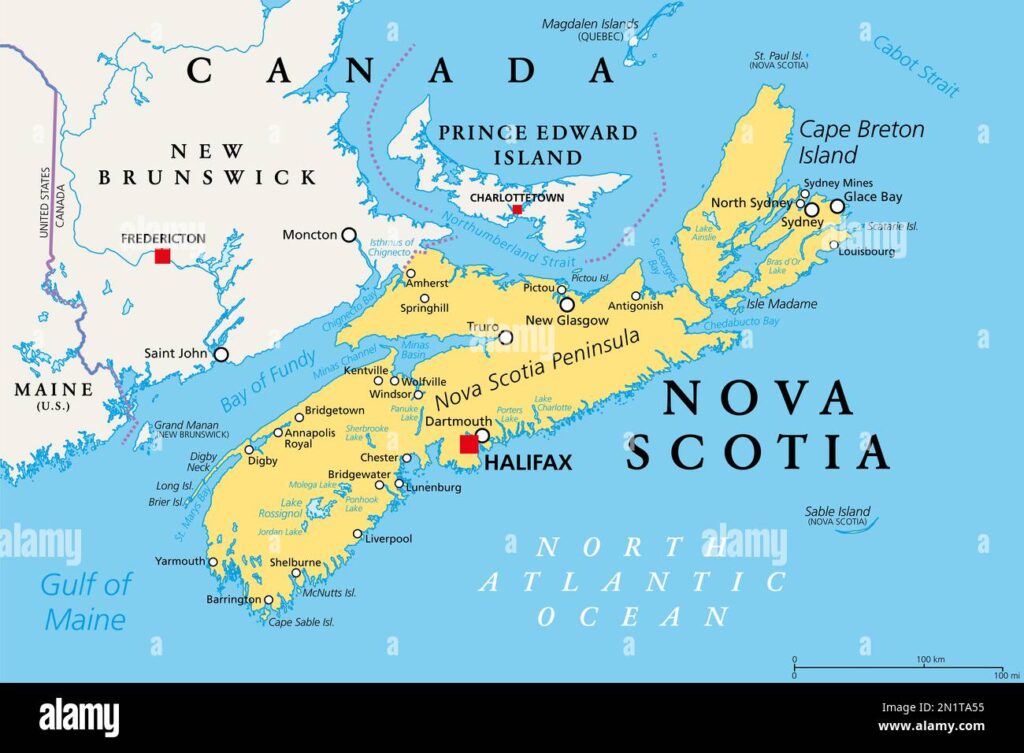

* It’s one of 10 Canadian provinces, the second-smallest by area and the second-most densely populated.

* The two main parts are Nova Scotia peninsula and Cape Breton Island, which are separated by the Strait of Canso. The two land masses are connected by the 4,544-foot long, rock-fill Canso Causeway.

* The capital is Halifax, which is home to 45 percent of the province’s population of about 1.1 million.

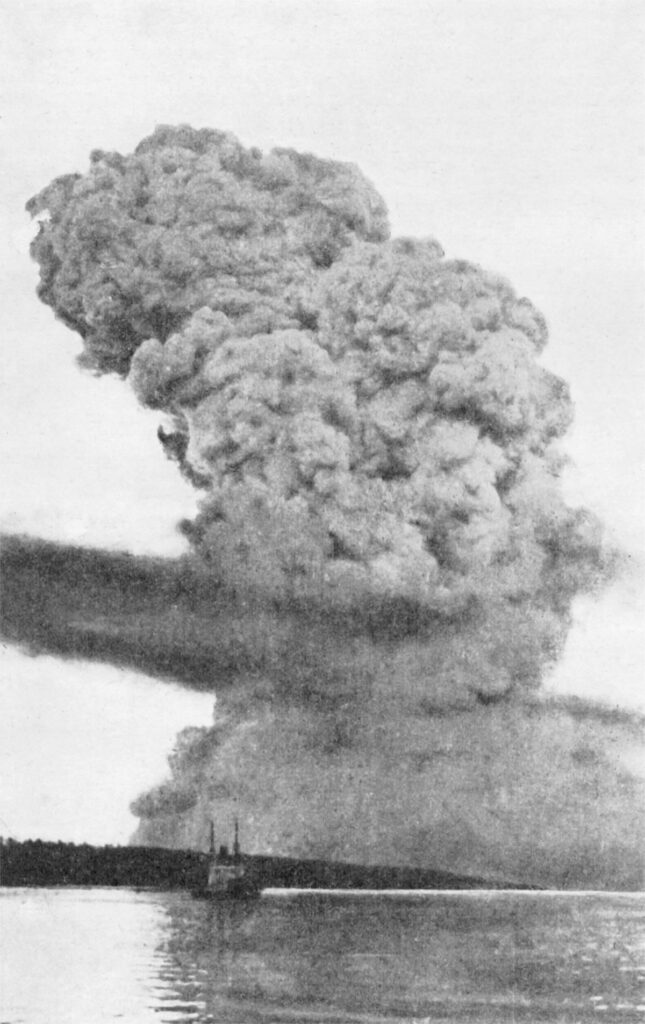

* In 1917, Halifax was the site of the largest human-made explosion in history prior to the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in 1945.

The day before we flew to Halifax, I started feeling sick with coughing, headaches, nausea and chills. By the time we arrived the following afternoon, I was so weak I could barely walk. So, instead of touring the city, I stayed in bed at our hotel with an icepack on my head until we met a cousin for dinner at the Halifax waterfront.

He’s a doctor, but being a vascular surgeon didn’t exactly fit my needs. So later in the day while visiting Annapolis Valley, a wine-producing region on the west coast of Nova Scotia, I stopped at a medical clinic to try to find out what was ailing me. Unfortunately, there was no doctor on duty at the small-town facility, so the nurse suggested I go to the regional hospital in Kentville, about 65 miles away.

When we got there, the emergency room was packed and I was told the wait time was at least three hours. They suggested I return about 4 a.m. the next morning, when the place would be far less crowded. I did so, and after a short wait, saw a doctor who ordered an X-ray, which showed I had pneumonia. He prescribed an antibiotic and told me I should start to feel better within 24 hours. Unfortunately, he was too optimistic and I felt lousy the whole week.

(Canada, which has a national health-care system, doesn’t accept Medicare from the U.S. But amazingly, the hospital didn’t even ask for a credit card to cover my treatment in case my secondary insurance, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, didn’t pay for the visit either. Humane health care — what a concept!)

But enough about my respiratory system. Despite my illness, I enjoyed the natural beauty and down-home friendliness of Nova Scotia, which is connected to Canada’s mainland by the Isthmus of Chignecto.

After leaving Halifax, we made the short drive south to Peggy’s Cove, a small fishing village with colorful homes that’s now primarily a tourist destination. Its most notable building is the red-and-white concrete lighthouse built in 1914, which replaced the original wooden structure from 1868. There are also two memorials commemorating the 1998 crash of Swissair 111 into the Atlantic Ocean off Peggy’s Cove, a granite slab with three notches in the top left that form the number 111 and a larger monument listing the names of all 229 people who died in the accident.

From there we drove across the peninsula to Annapolis Royal, a coastal town with a 300-year-old fort, the oldest formal cemetery in Canada and the 17-acre Royal Historic Gardens. We stopped at a pub in town where some locals were playing traditional Scottish music, a tribute to the settlers who came to the area in the early 17th century.

We then drove about 70 miles to Wolfville, where we stayed in a beautiful country inn and ordered takeout from a nearby pasta place called The Noodle Guy. The owner, who was sitting next to us at the counter, introduced himself as The Noodle Guy. “Not many people know my real name,” he said. “I might as well have The Noodle Guy written on my drivers license.”

One customer asked me about President Bone Spurs’ threats to make Canada part of the U.S. He laughed at the absurdity of the idea and expressed amazement that such a moron could twice be elected president. “It’s really sad,” he said. “Canadians have always had great respect for your country. But Trump has pissed us off. He’s not welcome here.”

The next day we headed toward Antigonish, our last stop before crossing into Cape Breton. On the way we drove through Windsor, which bills itself as the birthplace of hockey. We had seen a sign on the highway for the Hockey Heritage Museum, but no one in town seemed to know where it was. (I later learned that the hockey museum is actually a small exhibit inside a historic home.) Sounds strange to me. That would be like Cooperstown housing the Baseball Hall of Fame in the local library.

Antigonish is the home of Peace by Chocolate, a company founded by Syrian refugees whose story was made into a book and movie. Their store offers an amazing variety of chocolate products, including candy bars with Canadian-themed flavors (dark chocolate with maple flakes) and names (Elbows Up, Eh?) The company donates part of its profits to the Peace on Earth Society, which supports peace-building projects around the world.

Our first stop in Cape Breton was Baddeck, home of the Alexander Graham Bell Museum. Bell was born and raised in Scotland and later lived in London, Boston and Washington D.C., but he spent most of his final 30 years at his waterfront estate in Baddeck, a tiny village in the center of Cape Breton.

Although Bell is best known as the inventor of the telephone, he also was a pioneer in aviation, sound recording and devices to help the hearing-impaired and the deaf, including his mother and wife. Some of Bell’s earliest recordings have been digitalized and we listened to a grainy one from 1885 in which he says, “Hear my voice, Alexander Graham Bell.” Wonder what old Alex would think of the iPhone.

Alexander Graham Bell at the opening of the long-distance line from New York to Chicago Reproduction Number LC-G9-Z2-28, 608-B Gilbert H. Grosvenor Collection,

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

That night we stayed just up the road in North River Bridge at the charming Chanterelle Inn, owned by a German couple who lived in the Dominican Republic for 25 years. He’s a civil engineer and she’s a chef who runs the kitchen for the inn’s gourmet, prix fix restaurant that sadly I was unable to enjoy because of my lingering pneumonia. I sipped a little soup before getting nauseous and heading to our room to sleep.

The following day we drove the entire 185-mile Cabot Trail, a scenic highway loop that offers spectacular coastal, mountain and forest views as it weaves through Cape Breton Highlands National Park. There are 26 hiking trails along the way, but our extensive trekking plans were derailed by my illness, which limited us to a single one-mile stroll.

We had hoped to see the vivid fall colors during our drive, but it turned out we were a few weeks too early and most of the trees were still green. We also noticed that all the creeks and riverbeds were bone dry, the result of a severe drought that has plagued Nova Scotia since early June.

Along the Cabot Trail we made a brief stop at the Wreck Cove General Store, which sells everything from crab rolls to fishing gear. I bought a cup of strawberry ice cream and the cashier gave me a ziplock bag of ice for my persistent headache.

We stayed overnight at Keltic Quay, lakeside cottages in the tiny town of Whycocomagh. We got takeout dinner from Charlene’s Restaurant, a popular local eatery where we ordered lobster rolls and scrumptious seafood chowder crammed with huge chunks of fish and no potato filler. Eat your heart out, Campbell’s and Progresso!

On the way out of town the following day, we browsed at the Farmer’s Daughter country store, which carries high-end outdoor clothing, shoes and equipment. It also has a bakery/deli that sells homemade bread and pies along with hand-crafted sandwiches. We met the granddaughter of the store’s founder, who lives on the family’s 100-acre farm outside town. She told us that the farm once had 72 sheep, but because of overbreeding they sold all but 13 of them to people who promised to keep them as pets. She showed us photos of their adorable lambs, which reminded me why I never eat baby sheep.

That night we stayed in Truro, the hometown of several famous Black Canadians including classical singer Portia White, civil rights leader Rocky Jones and Art Dorrington, the first black hockey player to sign an NHL contract. In the morning, we drove back to Halifax to visit the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, which features major exhibits on the Titanic and the Great Halifax Explosion.

Because Halifax was the closest major seaport to the Titanic sinking, it became the base for recovery efforts following the 1912 disaster in which 1,518 people died. Of the 209 bodies brought to Halifax, 150 were buried in three of the city’s cemeteries and the other 59 were claimed by relatives and sent back to their hometowns. Among the artifacts on display at the museum are wooden fragments from the Titanic, a letter written by Halifax millionaire George Wright on board the ship and a pair of a child’s leather shoes recovered from the wreckage. The identity of the child wasn’t known until 2007, when DNA testing showed the shoes belonged to a 19-month-old toddler from England.

The Great Halifax Explosion of 1917 is largely forgotten now outside of Nova Scotia, but at the time it was the largest man-made explosion in history. It happened when two ships, one of them loaded with highly combustible explosives headed for Europe to supply Allied troops in World War I, collided in Halifax harbor, setting off a mushroom cloud that killed more than 1,700 people, injured 9,000 and destroyed much of the city and neighboring Dartmouth. A memorial bell tower was built on a hilltop in a city park, and a service is held every Dec. 6 to commemorate the date of the explosion.