A year ago, just before the coronavirus shut down international travel, Pat and I went on a safari in Tanzania. Pat then returned home to work, but I stayed in Africa for another week to visit Rwanda and Uganda, where I fulfilled a longtime dream of seeing the mountain gorillas made famous by Dian Fossey.

Unlike most of my other travel adventures, I didn’t write about the trip after coming home. I think I was so preoccupied with the virus and the radical change in our lifestyle that Africa quickly faded into the background.

But now, one year later, I thought I’d post some pictures and words about our magical trip.

We started in Tanzania, where three years earlier I had spent seven grueling days climbing Mount Kilimanjaro. This visit was far less taxing, consisting mostly of watching animals, touring museums and trying not to mispronounce Swahili words.

Our first stop was Arusha, a tourist town not far from major attractions like Kilimanjaro, Lake Manyara National Park and the Ngorongoro Crater, the world’s largest, intact caldera.

On the outskirts of Arusha we visited Hill Crest, a private preschool for underprivileged children where my cousin Paige had worked as a volunteer teacher in 2017. The founder, an energetic, middle-aged woman named Elizabeth, gave us a tour of the school, which consisted of a couple of barracks-like buildings whose walls were brightly painted with pictures of flowers, plants, English vocabulary words, and the cat and mouse from the Tom & Jerry cartoon. The classrooms were sparsely furnished with plastic chairs and desks, but the children seemed happy to be there, smiling, laughing and singing songs for their foreign guests.

Our next stop was the Arusha Cultural Heritage Center, a striking modern building that looks like a giant glass drum supported by sword-like beams and covered on one side by a massive, heart-shaped shield. Inside, where you walk from floor to floor along a winding ramp, is an impressive collection of African art and artifacts, including beautiful ebony carvings of lions, giraffes, hippos, wildebeest and other native wildlife. Next door to the center, the Jane Goodall Institute was building a chimpanzee museum to honor the woman whose groundbreaking studies of chimps in Tanzania made her a global icon.

Next was a three-hour, 100-mile ride along mostly dirt and gravel roads to Ngorongoro Crater, home to an amazing panoply of animals that includes lions, cheetahs, elephants, wildebeests, zebras, hyenas, giraffes, Cape buffaloes, rhinos, baboons, hippos, ostriches and gazelles. They all live inside a 2,000-foot deep, 100-square mile crater that was formed when a huge volcano erupted and collapsed on itself more than 2 million years ago.

From Ngorongoro we headed northwest to the Serengeti, renowned for one of the largest mammal migrations on Earth. There we witnessed the most spectacular wildlife sight I’ve ever seen — huge herds of wildebeests stretching for miles and miles, packed so close together that from a distance they seem to blend into one solid mass. An estimated 1.5 million wildebeest migrate throughout the year in Tanzania and Kenya, the second-largest mammal migration in the world behind the 10 million fruit bats that travel annually between Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Our guide, David, was a fantastic photographer who took amazing close-ups of the animals with his telephoto lenses. Among my favorites were shots of mating lions (the growling male looked like he was about to eat the female), two zebras jawing at each other, and a blowup of an elephant’s wrinkled forehead. When David wasn’t taking pictures, he was often helping other guides pull their jeeps from the muddy holes that dotted the landscape. (We never got stuck because David always avoided the mudholes like a NASCAR driver swerving to avoid a crash.)

After Pat left Tanzania to return home, I flew to Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. It’s one of the most modern, progressive cities in Africa, but it’s also the home of the Kigali Genocide Memorial, a stark reminder of the country’s painful past.

More than 250,000 thousand of the estimated one million people killed during the 1994 Rwandan genocide are buried in mass graves on the site. The memorial also includes a museum that chronicles the genocide in words, pictures and film. Amazingly, 27 years after extremist Hutus slaughtered Tutsis and moderate Hutus during a three-month campaign of terror, Rwanda is now a united, thriving country that is considered a model for the rest of Africa.

The country’s leader, Paul Kagame, is a controversial figure who led the rebel army that stopped the government-backed genocide. He’s been accused of human rights violations and silencing his political opponents, but he’s also boosted the country’s economy and promoted reconciliation between Hutus and Tutsis. Whatever his legacy, it’s clear that Rwanda has openly confronted an ugly chapter in its history and used it as a lesson to prevent it from happening again.

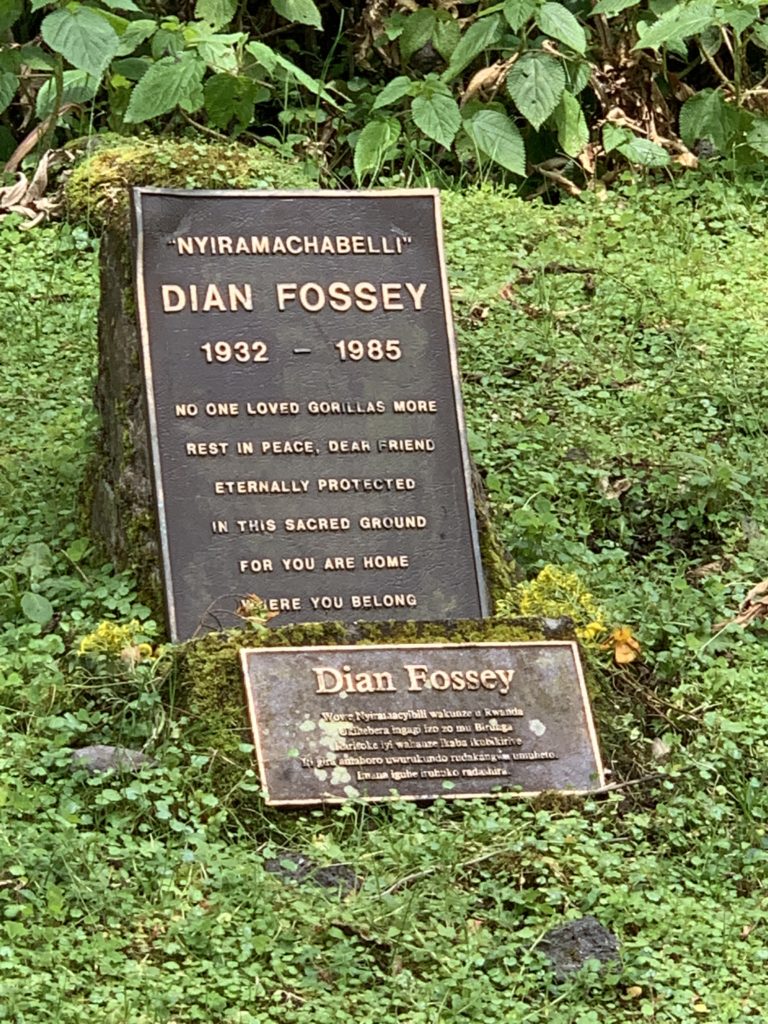

While I was in Rwanda, I also visited the remote mountain camp where Fossey was murdered, presumably by gorilla poachers, in 1985. I hiked up to see her gravesite (a strenuous, muddy, 5-hour roundtrip trek), where she is buried alongside some of her favorite gorillas. The camp no longer exists, but there are signs telling visitors where Fossey’s cabin and other buildings were located. I also visited the modest headquarters of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, which includes exhibits about mountain gorillas and the campaign to protect the endangered primates. (The efforts are paying off. The population of mountain gorillas has increased to more than 1,000 in recent years.) Later this year, the Fossey organization and all its research activities in Rwanda will be moving to a new, state-of-the-art facility partly funded by comedian/talk-show host Ellen DeGeneres.

After crossing the border into Uganda, I visited the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, which is part of the Virunga Mountain range that spans Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. You can see the mountain gorillas in all three countries, but I chose Uganda because the required permit cost less than half as much as the one in Rwanda (at the time, it was $600 vs. $1,500). The Congo permit was even cheaper ($400), but most travel companies tell tourists to avoid the country because of its volatile political situation.

Before you start your gorilla trek, you listen to a brief orientation from a park ranger, who explains that each group (maximum eight people) is only allowed to watch the gorillas for one hour after they’re first spotted. Gorilla tourism is very popular, so there are strict rules to protect the great apes and their environment.

Every morning scouts track the gorillas so they’ll have an idea where to find them when the tourists arrive. You usually have to hike up the mountain for several hours to find the gorillas, though the time can vary widely based on the weather, the walking conditions (it can be quite muddy) and where the gorillas are hanging out that day.

Our group —which included four Irish women currently living in Dubai and a French family (parents and a son), along with four rangers and five trackers — hiked for about 90 minutes before spotting a group of 14 gorillas known as the Hirwa family. Hirwa means “lucky one’’ in the local language, and we were certainly lucky to spend time with this playful family, which included three youngsters ranging in age from nine months to three years.

Tourists are supposed to stay at least 20 feet away from the gorillas, which are highly susceptible to human diseases. But during our visit, the gorillas sometimes came as close as 10 feet when they were walking or running in front of us.

Seeing a gorilla up close is an unforgettable experience. Humans and gorillas share about 98 percent of their DNA, something that’s obvious when you look into their eyes or watch how they behave with their young ones. We watched the gorillas munch on leaves, climb trees, roll on the ground and dutifully pose for thousands of photographs. At one point, the group’s dominant silverback led a group of females into the dense brush, for what purpose I can only guess.

The following day I returned to the park to see golden monkeys, which get their name from the bright fur color on their back. The rest of their body is black, though the area around their nose and mouth is light.

We saw dozens of the monkeys, but it was hard to get close to them because they kept springing from tree to tree. Even from a distance, though, we could hear them chomping on bamboo shoots and leaves, which form the bulk of their diet.

Amazing adventures! Your account of your trip (including fantastic photos) could land you a spot on NatGeo! I chuckled when I read your concerns about mispronouncing Swahili words. For me, spell check would be a must, too! Thanks for sharing your story.

This trip sounds pretty amazing, and I am glad you finally got around to sharing it with us! Great photos!

WOW! Just read through this… A once-in-a-lifetime adventure. Love the pictures too and especially love that you were able to visit the school that Paige worked at. THANKS for sharing…