As my wife and I rode a taxi to the Havana airport after an eye-opening week in Cuba, our driver summed up the current situation on his star-crossed island: “Life is not good now,’’ he said. “The people are unhappy and things are getting worse every day.’’

Cubans had high hopes for an economic boost after U.S. President Barack Obama opened up relations with the communist country in 2014. But after a few years of hopeful progress, Cuba suffered a major blow when Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, rescinded the policy and instituted harsh new sanctions that have decimated the Cuban economy.

Trump claims he made the change to punish Cuba’s oppressive government and pressure the country’s leaders to forsake the communist system that was established following Fidel Castro’s revolution in 1959. But the people hurt the most by Trump’s new rules are everyday Cubans, who are struggling to deal with food and gas shortages and a dramatic decline in tourism largely due to the new U.S. edict that bans cruise ships from visiting Cuba. (Right after we returned home, Trump went even further, banning commercial flights from the U.S. to all Cuban cities except Havana.)

My wife and I saw many wonderful things in Cuba, including gifted student dancers and singers at a performing arts school, an innovative organic farm run by a tight-knit community, a classic car business owned by an energetic entrepreneur, a celebrated fashion designer who makes colorful hand-painted clothes at her home studio, and a trendy nightclub/art gallery that’s as hip as anything you’ll find in New York, Miami or San Francisco. However, we also witnessed the crumbling buildings, frequent power outages and scarcity of basic goods such as meat and toilet paper.

If visitors do nothing but stay at tourist hotels, eat at tourist restaurants and travel to tourist sites, they can have a comfortable vacation and barely notice the hardships. If you pay attention, though, you’ll also notice the long lines at banks, the half-empty shelves at grocery stores and the light traffic on highways and city streets because gas is so hard to find.

Still, Cuba is worth a visit. It’s a country brimming with friendly, creative people and a fascinating ethnic mix that has produced a vibrant, varied culture.

Even under the new regulations, Americans can travel to Cuba as long as their trip fits into one of 12 approved categories. Currently the most popular one is “Support for the Cuban People,’’ which requires visitors to engage in cultural activities and spend their money at private rather than state-owned businesses so they won’t provide economic support for the communist government.

Some tourists make their own arrangements but most, including my wife and I, pay for group tours because those companies are experts at dealing with the confusing Cuban bureaucracy.

Speaking of money, Cuba has a bizarre two-currency system that includes one type of money for Cubans and another designed for tourists. One tourist peso is worth one U.S. dollar, though in reality it’s currently worth about 87 cents because the Cuban government charges a 13 percent fee to convert U.S. money. You can use the tourist peso almost anywhere, and some places even accept U.S. dollars. (Bring plenty of cash because you can’t use U.S. credit cards in Cuba.)

Our nine-person tour, arranged by a company called Friendly Planet in suburban Philadelphia, started in central Cuba and wound its way west toward Havana, with stops along the way in Santa Clara, Sancti Spiritus, Trinidad, Varadero and two neighborhoods on the outskirts of Havana, Alamar and Cojimar. (We had five lawyers in our group, which I jokingly nicknamed The Esquires.)

After flying into the tiny airport in Santa Clara, we traveled about 60 miles on our tour bus to Sancti Spiritus, one of the first Cuban cities settled by Spanish colonists in the early 1500s. There were more horse-draw carts than cars on the roads we traveled, which our guide Felix explained was due to an acute gas shortage in the country. We also noticed bones protruding from the cattle grazing in the fields, a condition that Felix attributed to a “lack of fodder.’’

The following day, we took a short drive to the southern coastal city of Trinidad, where we visited a family-run, bed-and-breakfast located in a restored 1850 home. (Private businesses are allowed in Cuba, though they are strictly regulated and pay a heavy tax to the state). Like good capitalists, the husband and wife owners did some subtle advertising, reminding us that we could book rooms in their home on Airbnb and check out their reviews on TripAdvisor.

Back in Santa Clara we visited a performing arts school that draws music, dance, theater and visual art students from all over central Cuba. We were greeted by a six-piece band that serenaded us with a variety of Cuban music plus a percussion-driven version of The Beatles standard “Yesterday.’’ Then we walked into to a barren, sweltering room (most buildings in Cuba aren’t air conditioned) where we watched a class of 16 sweaty students practice a Western African dance that featured a hypnotic rolling shoulder movement. The girls wore black tights and the bare-chested boys wore black briefs as they gracefully moved to the rhythms of double-sided Bata drums and a chanting singer.

One obligatory stop in Santa Clara is the Che Guevara memorial, which includes a 22-foot high statue of the revolutionary hero wearing military fatigues and carrying a rifle. It’s also the site of his mausoleum, which was closed the day we visited because they were preparing for one of Cuba’s numerous celebrations of the revolution. However, we still got to hear the story of how it took 30 years to retrieve Che’s remains from Bolivia after he was executed by a Bolivian soldier in 1967.

Our next stop was Varadero, a beach resort town on the northern coast that is Cuba’s version of Miami Beach. Luxury hotels line the peninsula — the one we stayed at had an 18-hole golf course, tennis courts and a two massive swimming pools — and a nearby mansion called Xanadu was built by Irenee du Pont, who was once president of his family’s chemical conglomerate.

While we were in Varadero, our group visited a studio where we learned about Cuba’s national dance, known as Danzon. It’s a slow, formal dance that requires precise footwork following a syncopated beat. I tried doing it with one of the dance instructors, who tried to ignore the fact that I kept stepping on her feet.

Not far from Varadero, in the coastal city of Cardenas, we visited artist and fashion designer Mariela Aleman Orozco, who demonstrated how she makes her designs on the rooftop of her family home. After laying a moist piece of white cotton cloth on a long table, she sprinkles uncooked rice, leaves and beans on the fabric to imprint designs. Next, she grabs plastic bottles filled with brightly colored inks, squirts the liquid over the fabric a la Jackson Pollock and spreads it around with her fingers. Then she leaves the cloth out to dry in the sun before the pieces are used to make dresses, shirts and scarves.

Several statuesque young women modeled Mariela’s striking dresses on a homemade runway. Then I joined another guy in our group, a lawyer from Chicago, to model the blue Hawaiian-style shirts that we had just bought from Mariela. We both sashayed down the runway, looking like a couple of drunken conventioneers in Vegas.

Just outside Havana we stopped in Alamar, a massive, ugly development of Soviet-style apartments built in the early 1970s. Alamar is the birthplace of Cuban rap and the home of Organoponico Vivero, a renowned communal farm that makes it own fertilizer from “worm poop’’ and keeps fish in open holding tanks to prevent the water from becoming stagnant and attracting mosquitos. We got a humorous tour of the 27-acre, 150-worker farm from Isis, whose father helped establish Organoponico in 1997. Summing up her father’s desire for modern tools and her love of cooking with organic foods, Isis told us: “He wants Home Depot and I want Alice Waters’ kitchen.’’

On a hill overlooking downtown Havana we visited Finca Vigia (“Lookout Farm’’), the home where Ernest Hemingway lived off-and-on in the 1940s and ‘50s and where he wrote parts of “For Whom the Bell Tolls’’ and “The Old Man and the Sea.’’ It’s now a state-run museum that houses thousands of books, letters and photographs left behind when Hemingway moved out of the country in 1960. Visitors aren’t allowed in the house, but they can view the rooms through numerous windows and open doors. Peeking inside, we spotted a lizard preserved in a jar in the bathroom, a magazine with JFK on the cover, and a Picasso-crafted plate depicting a bull hanging on the wall. On the grounds of the 12-acre property, you can also see Hemingway’s beloved boat, Pilar, resting on a former tennis court, the gravesites of his four dogs, an empty swimming pool and a three-story tower that his wife had built for Hemingway to use as a writing studio. (He preferred to write standing up in his bedroom.)

People often say that visiting Havana is like traveling back to the 1950s because of all the old cars and buildings that seem like they haven’t been painted since the Eisenhower administration. That’s true, but the city also has a trendy youth culture that thrives at places like Fabrica de Arte Cubano, a multimedia nightspot located in an old cooking-oil factory in the city’s upscale Vedado neighborhood. At FAC, you can dance, listen to live music, eat a gourmet dinner, watch Charlie Chaplin movies and wander through avant-garde art exhibits. (When we were there, the featured artist was Enrique Rottenberg, whose exhibition included satiric self-portraits showing him eating a “Last Supper’’ surrounded by glum-faced servants and a nude photograph of him crawling with pigs.)

We saw the works of another experimental artist in Jaimanitas, a small fishing village on the fringe of Havana. His name is Jose Fuster and his unique creation is called Fusterlandia, a fanciful potpourri of sculptures, walls, spiral staircases, fountains and pools covered with kaleidoscopic mosaic tiles. Fuster has turned his home and his entire neighborhood into a public art project that looks like a mini-Disneyland. It’s been an economic boon for his neighbors, who have lined the street where he lives with shops peddling locally made arts and crafts.

Of course, no trip to Havana would be complete without a sniff of those world-famous Cuban cigars. We visited the country’s largest cigar factory, Partagas, which employs 400 people and produces 25,000 cigars per day. We watched the workers hand roll, wrap, label and box the cigars, which are sold under brand names such as Montecristo, Cohiba and Romeo y Julieta. (Just imagine Romeo puffing on a cigar during the balcony scene.)

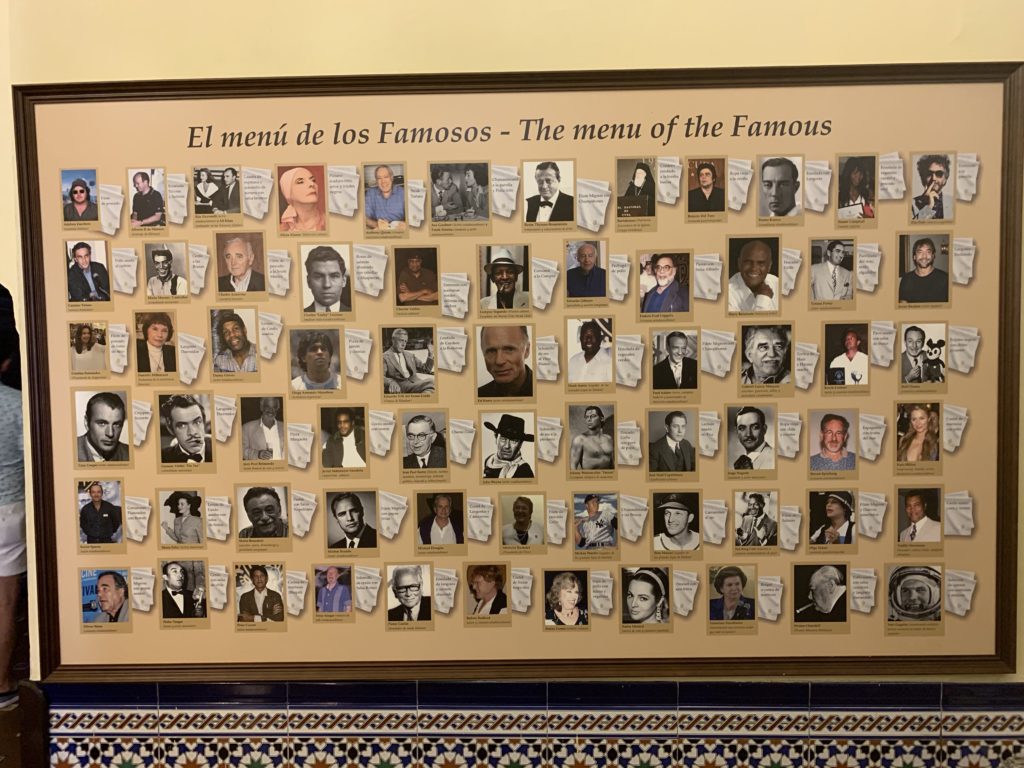

Our other stops in Havana included Revolution Square, which features a 358-foot tower and a 59-foot tall statue of Jose Marti, considered the George Washington of Cuba; Cristobal Colon Cemetery (named for Christopher Columbus), where many rich and famous Cubans are buried in elaborate marble mausoleums; John Lennon Park, where a bronze statue of the former Beatle sitting on a park bench is often adorned with a visitor’s eyeglasses; and Hotel National de Cuba, a palatial resort that has hosted celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, Mickey Mantle, Marlon Brando and Winston Churchill. The hotel also was the site of a famous 1946 Mafia meeting featured in “Godfather II,’’ though I didn’t notice any statues of Michael Corleone on the grounds.

Another Havana highlight was riding in classic cars operated by NostalgiCar, a company that ferries tourists around Havana in restored 1950s Chevys. Old cars, painted in shiny rainbow colors, are as much a part of the scenery here as the Malecon, the 5-mile long promenade and seawall that stretches along the city’s coast.

NostalgiCar is owned by Julio Alvarez and his wife Nidialys, whose fleet now includes 22 cars that are so lovingly cared for that they’ve been given people’s names like Lola, Nadine and Daniel. During a tour of his garage, Alvarez told us that while attending a conference in Washington, D.C., in 2013 he was unexpectedly invited to the White House. President Obama wasn’t there at the time, but he spoke to Alvarez’s group via a video screen. “I told the president I was embarrassed because I was still dressed in jeans and boots,’’ Alvarez said. “But he said, `Don’t worry, I’m wearing my shorts.’’’

Finally, a few random observations about Cuba:

- Baseball is the national sport and for a long time Cuba dominated international amateur competitions like the Olympics and World Cup. But the influx of Cuba’s best players into the major leagues has diluted the quality of Cuban baseball. “To see our best players now we have to watch U.S. TV,’’ a hotel bartender said with a rueful smile.

- Cigars and rum are as omnipresent as pictures of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. Although smoking is officially banned in public places, most Cubans ignore the rule and puff away. And mojitos, a rum-based cocktail, are served like water during meals.

- Cubans speak Spanish the way Cajuns speak English — in a style all their own. Their pronunciations, grammar and slang are so distinct that Spanish speakers from other countries often can’t understand them.

- I was surprised that so many Cubans I met openly criticized the government. Cuba is still an authoritarian state, but people there don’t seem to fear reprisals for speaking out the way they did when Fidel Castro was boss.

- Toilet paper is a rare commodity. You’ll find it in tourist hotels and restaurants, but not in public bathrooms. Also, because the plumbing system is antiquated, you’re always advised to throw used toilet paper in the trash, not flush it down the toilet.

Rick: This is a beautifully written summary of a spectacular week experiencing the wonders of Cuba and the lovely people we had the pleasure of meeting! Thanks for writing it!

Spectacular travelogue of what looks to be a most fascinating place. Thanks for sharing!

Very good Rick! You suffered the heat and then painted a picture of the best parts for us to enjoy. Enjoy I did. Thank you.