The greatest hardship passengers faced on our ferry ride through the Panama Canal occurred when, halfway into the six-hour trip, the captain solemnly announced that the concession stand had run out of beer. This news elicited moans and groans from a handful of spoiled tourists, who apparently forgot about the real suffering endured by the estimated 27,000 workers who died of disease and accidents while hacking their way through the Panamanian jungle during the canal’s construction from 1881-1914.

It’s easy to forget what a remarkable feat it was to build the first waterway between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in the early 20th century, using primitive tools in an inhospitable environment riddled with mosquitoes that caused deadly yellow fever and malaria.

www.rarehistoricalphotos.com

Today, in addition to being a huge tourist attraction, the 50-mile long canal is an economic powerhouse that generated a record $3.3 billion in revenue in the most recent fiscal year despite a drought that limited the number of ships passing through. Most of the money comes from tolls that can exceed $1 million for one trip by a supersized container ship carrying everything from cars to chemicals. (A few days after our canal trip, Panama authorities announced that daily ship crossings would be cut from 38 to 24 because of the drought. This, combined with attacks on commercial ships in the Red Sea by Yemen’s Houthi rebels, will hurt global trade by delaying shipments and increasing transportation costs.)

The ferry through the canal was one of the highlights of a two-week tour of Costa Rica and Panama that my wife Pat and I took in January. Other memorable activities included scenic hikes in the luscious rain and cloud forests of Costa Rica, a cooking class where we chopped our own ingredients with a machete, a wine tasting session that left me slurring my words, a hilltop view of Panama City’s striking skyline, a visit to a monkey sanctuary where white-faced capuchins danced to Spanish commands, swimming in a crystal blue pool beneath a magnificent waterfall, and a private tour of a 50-foot high treehouse by the owner of a Caribbean resort.

More about those later. But first, a brief history of the Panama Canal.

France started work on the canal in 1881, but halted construction in 1899 due to engineering roadblocks, financial problems and 22,000 worker deaths, mostly from tropical diseases. In 1903, after helping Panama gain independence from Colombia, the U.S. obtained rights to build and administer the canal. The U.S. maintained control until Dec. 31, 1999, when Panama took command of the waterway under a treaty signed by President Jimmy Carter 22 years earlier.

The canal, which is fed by three artificial freshwater lakes, works on a lock system that controls the level of the water. It’s too complicated to explain here, but suffice it to say that it’s an engineering marvel that’s amazing to witness. When the locks open, it’s like watching the gates of an ancient fortress slowly swinging apart.

During our trip through the canal, we saw massive cargo ships carrying as many as 13,000 containers. The growing size of these container ships is why the canal was widened and two new locks added during a $5.25 billion, decade-long expansion project that was completed in 2016. When you take a ferry partway through the canal, you have to wait for at least one container ship to go through the locks with you in order to preserve water. The day we went, we had to wait more than an hour at both locks we used. But that’s nothing next to the delays of as many as eight days that the biggest ships encounter while lining up to enter the canal.

We got a good introduction to the canal by watching a 45-minute IMAX film narrated by Morgan Freeman at a modern visitors center where tourists pack the outside balconies to see vessels ranging from private yachts to giant container ships pass through the Miraflores lock. (Another excellent primer is David McCullough’s book, “The Path Between the Seas.”)

If you want to know how revolutionary the Panama Canal was, consider this: Before it was built, it took ships about two months to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by bending around Cape Horn at the southern tip of Chile. Now, it usually takes between eight and 10 hours. Quite an impressive shortcut.

We started our vacation in La Fortuna, a town near the famous Arenal Volcano about 80 miles northwest of the Costa Rican capital San Jose. It’s usually difficult to see the top of the volcano because of an ever-present fog and mist, but we got lucky on our third day in the area when clear, sunny weather allowed us to see the peak from the bedroom of our casita. Later, we hiked up to a lookout point where we got a close-up view of the cone-shaped volcano whose deadly eruption in 1968 killed 87 people and buried three small villages. (Arenal last erupted in 2010.) At one point, we saw a crawling green creature nicknamed the “Jesus Christ lizard’’ because it’s known to walk on water using its hind legs.

One member of our hiking group was an airline pilot from Edmonton who often flies to remote parts of northern Canada. He used to live in Yellowknife, a town about 250 miles from the Arctic Circle where January temperatures often plunge to minus-30 degrees Fahrenheit. When I asked him what you do in the winter there, he smiled and said: “Watch a lot of movies.”

We also visited a park with six hanging bridges and ziplined almost two miles in a rain forest. (Pat overcame her acrophobia and valiantly did the whole course without a single scream.) We returned to our resort in a canopied cattle car pulled by a beat-up tractor over a bumpy dirt road, which our driver dubbed “The Costa Rican massager.’’

The next day, during a “safari river tour’’ on a four-passenger raft, we spotted crocodiles, howler monkeys, toucans, herons, bats and even a porcupine. (Howler monkeys make a loud, grating sound that one observer compared to a garbage disposal.) On the drive back to our casita, we also saw a sloth hanging upside down from a tree, a sight that drew more than a dozen gawkers who pulled their cars over to the side of the road.

My biggest challenge in Costa Rica was our cooking lesson at a local farm, where we wielded machetes to harvest lemons, limes, yuca, oregano, cilantro, habanero chili and sweet potatoes to make a delicious lunch of chicken with annatto sauce, pico de gallo (aka salsa fresca), patacones (fried plantain slices), frijoles molidos (refried beans), and plantain-yuca chips. I’m not much of a cook, but I did manage to do a lot of slicing and dicing without chopping off any of my fingers.

Although January is considered the dry season, and it was sunny most of the time, it rained almost every afternoon. The local joke is that it rains in La Fortuna “24 months a year.’’ It’s called a rain forest, after all.

From La Fortuna we took a two-hour van ride over winding mountain roads to an eco-friendly lodge in the tropical cloud forest of Bajos del Toro. The area is teeming with waterfalls, lush foliage and hundreds of species of birds and insects. Our suite came with a panoramic view and a private hot tub, which we used to relax after strenuous hikes.

For some strange reason, the lodge also featured a small archery range, where I finished second in a six-person contest to a former restaurant owner from Seattle. “She’s very competitive,’’ her husband told me. I learned that the hard way when she beat me on the final shot.

The following day, we hiked to a stunning blue waterfall. As I walked barefoot over slippery rocks beneath the waterfall, I slipped and cut both my legs pretty severely. I washed the blood off by taking a dip in a freezing natural pool, which numbed my legs and stopped the bleeding without any need for first aid. I’m thinking of taking out a patent for this home remedy.

Another pain reliever was a wine tasting that afternoon where we sampled vino from France, Spain, Chile and Argentina. I’m no oenophile, but I can certify that if you drink enough wine you forget about all the gashes on your legs.

The following day we took a two-hour van ride to San Jose, where we stayed overnight at an airport hotel in order to catch an early-morning flight to Panama City. (We were originally scheduled to fly to Panama the previous day, but our flight was canceled when all Boeing 737 Max 9 planes were grounded after a door panel blew out on a Max flight over Oregon.)

On the way to San Jose, we stopped for lunch at an artisan town called Sarchi, where we toured an old ox cart factory that is now primarily used to make handmade furniture. I spoke to an elderly craftsman who has been making intricately patterned tables combining teak, cypress, oak and rosewood for 40 years. “I started out making chess tables,’’ he explained in Spanish. “This is my life.”

In Panama City we stayed at a hotel in the historic old town section known as Casco Antiguo or Casco Viejo. It has narrow brick streets, New Orleans-style balcony gardens and lots of trendy hotels, restaurants, bars and nightclubs. At one bar you sit on swings instead of stools, which makes you feel tipsy even before your first drink.

Walking around the neighborhood, we passed a street where hundreds of Panama hats were strung overhead. We learned that Panama hats actually originated in Ecuador and are still mostly made there. They became popular in the U.S. after President Theodore Roosevelt was photographed wearing one during a visit to Panama in 1906 while the canal was being built.

We also saw members of Panama’s Guna tribe dancing and playing bamboo flutes in a park. Panama has seven native tribes that make up 12 percent of the country’s population, more than any Central American country except Guatemala.

During our stay in Panama City, we got a fantastic view of the city’s modern skyline from the top of Ancon Hill, an area that was a U.S. military base when we controlled the canal. We later drove through the city’s skyscraper-packed business section, which is lined with bank offices located here because of the country’s reputation as a tax haven.

Back in our hotel, I watched part of the Steelers-Bills NFL playoff game in freezing Buffalo, where many seats were still buried in snow from a blizzard that forced the contest to be postponed by a day. It was 93 degrees at the time in Panama City, so watching the game was a surreal experience, like seeing something from another planet.

That night, I went to a local club to hear a band play on the opening night of the Panama Jazz Festival. About 50 people stood or sat on folding chairs in the open-air venue listening to a four-man combo playing organ, upright bass, drums and saxophone. When I asked someone in the crowd to identify a particular song, he laughed and said: “This is jazz. They make it up as they go along.’’

The next morning, we hopped on a one-hour flight to Bocas del Toro on the Caribbean coast of Panama. Bocas del Toro is an archipelago of nine main islands, 52 cays and thousands of islets that attract water lovers from all over the world. “Welcome to paradise,’’ a wizened airport greeter beamed before serenading us on his acoustic guitar with Bob Marley’s “Don’t Worry” and Harry Belafonte’s “Daylight Come.”

We stayed on a private mangrove island (Frangipani) owned by a retired tech executive from Grand Rapids, Michigan named Dan Behm. It was originally called Bocas Bali because of its Bali-inspired, over-the-water villas with thatched roofs, but is now known as Nayara Bocas del Toro following a branding agreement with a luxury resort group.

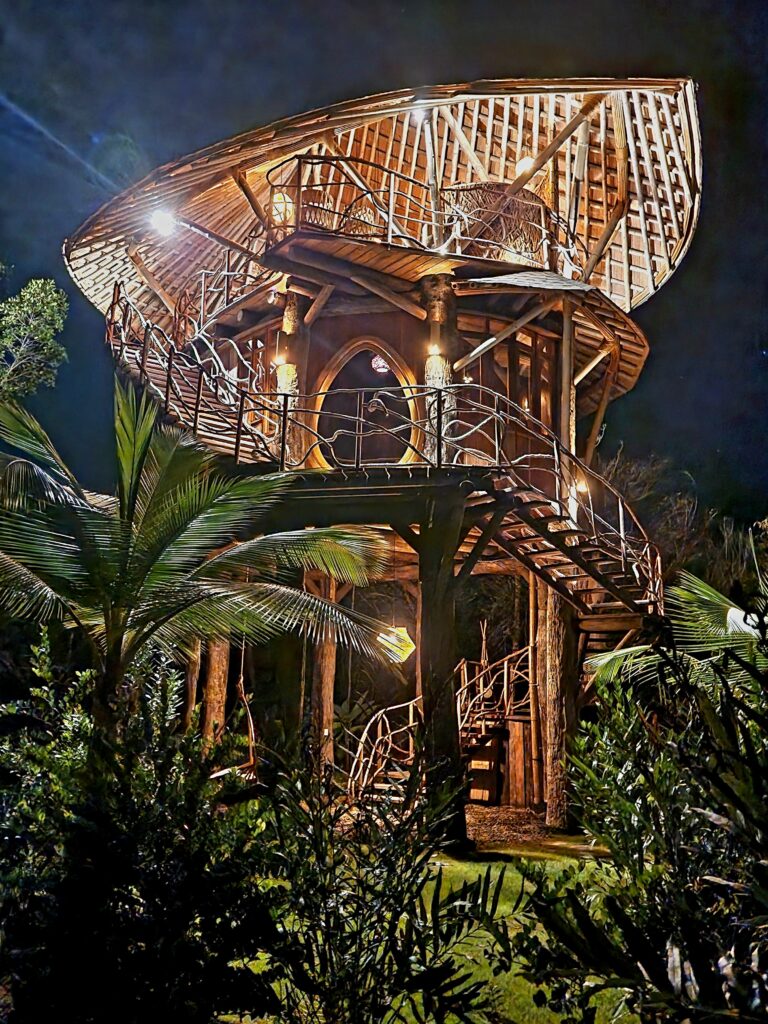

Behm was visiting the place while we were there to film a segment for a show on private islands and he graciously gave us a tour of the palatial treehouse where he was staying. (There are four of these multilevel treehouses, in addition to the 16 villas. We stayed in a villa.) Created by renowned designer Elora Hardy, the treehouses are made from local bamboo and petrified hardwoods salvaged from forests flooded during construction of the Panama Canal.

A winding wooden staircase takes you up to an oval glass door, leading to spacious rooms with 21-foot ceilings, an open-air penthouse and a copper soaking tub. And in case you’re too tired to go downstairs to pick up your room service, it can be delivered to the top floor via a dumbwaiter. Like the rest of Nayara Bocas, all the power is supplied by the sun, while purified rainwater is used for drinking and bathing.

The resort ain’t cheap (I can’t bear to type the price), but it does feel like paradise. All meals and non-premium drinks are included, as are kayaks, snorkels, paddle boards, yoga lessons and snacks at any time of the day or night. We got the impression that if you woke up at 3 a.m. and asked for a foot massage, the masseuse would arrive at your room within five minutes. There were also distinctive touches like a TV screen that magically pops out of the floorboard of your bed via remote control, the world’s first “aerial beach’’ built on pilings in the water and a partial glass floor in each villa to view marine life below in case you’re too lazy to walk out on the deck.

Pat and I kayaked, snorkeled, swam and tried to paddle board, though standing up for any length of time proved to be an insurmountable challenge. We also visited a monkey sanctuary on another island, where we saw howler, spider and white-faced anthropoids that had been rescued from unfortunate circumstances. The French-Canadian woman who runs the sanctuary has taught the white-faced capuchins to dance when instructed to do so in Spanish, and they performed for us by bouncing and gyrating to their own secret beat.

We ate dinner at the Elephant Room restaurant, another over-the-water building where we were entertained by a young musical duo who performed soothing covers of classic songs ranging from The Doors, Pink Floyd and Elvis to Patsy Cline, Dolly Parton and Judy Garland. A couple in real life, she was from Nicaragua and he was from Chile, a multinational mix that is very common in Central America.

We returned to Panama City for one night before flying home, eating dinner on a Juliet balcony at a restaurant across the park from our hotel.

Unfortunately, a disco next door blared ear-shattering music that penetrated our hotel bedroom until 2:30 a.m., followed by the shouts of kids playing soccer in the park until 3 a.m. Needless to say, we didn’t get much sleep that night.

So we returned home happy but exhausted.

Another outstanding trip and entertaining travelogue, Rick. Did you make the arrangements yourself, or did you use a tour company?

Such the wonderful report, and though I knew of your trip, this is so much more than I expected. You and Pat sure know how to live well and with much adventure. I’m so pleased to read your report, as I have been with all the others. Also of note, you’ve been working out and it shows! Congrats. And thank you for giving us another armchair adventure. Where are you going next? How will you top this? Smile.