Mark Twain supposedly said, “The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.” The quote is apocryphal, but it aptly applies to my visit to Iceland in late May, the start of a 15-day, six-country, three-time zone tour of Nordic Europe. Temperatures in the high 30s, combined with bone-chilling winds, made it feel like more like winter than a few weeks before the official start of summer.

Of course, Nordic countries aren’t known for their balmy climates. And it is called ICEland, after all. (Notice I don’t use the term Scandinavia to describe the region because technically that only includes Denmark, Norway and Sweden. We also visited Finland and Estonia.)

Weather aside, Pat and I thoroughly enjoyed our brief, two-day stay in Iceland, an isolated island in the middle of the North Atlantic. We took advantage of a generous offer from Icelandair, which allows its passengers to stop over in its capital, Reykjavik, for up to a week en route to someplace else without any extra charge.

We were especially fortunate because my cousin Bill and his half-Icelandic wife, Elissa, let us stay at their lovely getaway apartment in Reykjavik, a city best known as the host of the 1972 world championship chess match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky. (Fischer is buried in a small town about 40 miles southeast of Reykjavik.)

Almost every tourist who visits Iceland does the Golden Circle tour, and we were no exception. Our daylong bus trip covered four of the country’s natural wonders: a geyser park where eruptions occur every few minutes; Kerid volcanic crater; the dazzling Gullfoss waterfall where we saw a picture-postcard rainbow; and Thingvellir National Park, the birthplace of Iceland’s first parliament in 930 A.D. and the place where the North American and Eurasian continental plates intersect. (It was so cold on the day we visited Thingvellir that we spent most of our time in the cafe/gift shop drinking coffee and hot chocolate.)

We also visited Fridheimar, a farm where they grow tomatoes in geothermal heated greenhouses. Icelandic weather isn’t suited to growing tomatoes outdoors, so the farm grows them in greenhouses heated by the country’s abundant natural hot water. The 10,000 plants are pollinated by bumblebees and produce 370 tons of tomatoes each year, some of which are used to make the delicious soup served in their greenhouse restaurant.

The farm also is known for its Icelandic horses, which were first brought to the country by Norse settlers around 900 A.D. They are small, stocky horses that have two more gaits than traditional breeds, skills that were displayed for us by a white horse on a racing track. To show just how smoothly the horse moved, the female rider held a full mug of beer during the demonstration and didn’t spill a single drop.

From Reykjavik we flew to Copenhagen, Denmark, where our hotel was across the street from Tivoli Gardens, a 180-year-old amusement park that was one of the inspirations for Disneyland. You won’t see Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck there, but you can ride on one of the world’s oldest wooden rollercoasters, attend a pantomime theater and watch a youth marching band.

On our first day in the city, we walked down a popular pedestrian shopping street and went inside a Lego store that charts the history of the famous Danish toy. Legos are everywhere in Copenhagen, as are statues of Hans Christian Andersen, ice cream parlors and bicycles. If you stray into a bike lane when you’re walking, you better have quick reflexes to avoid getting flattened like Wile E. Coyote in a Road Runner cartoon.

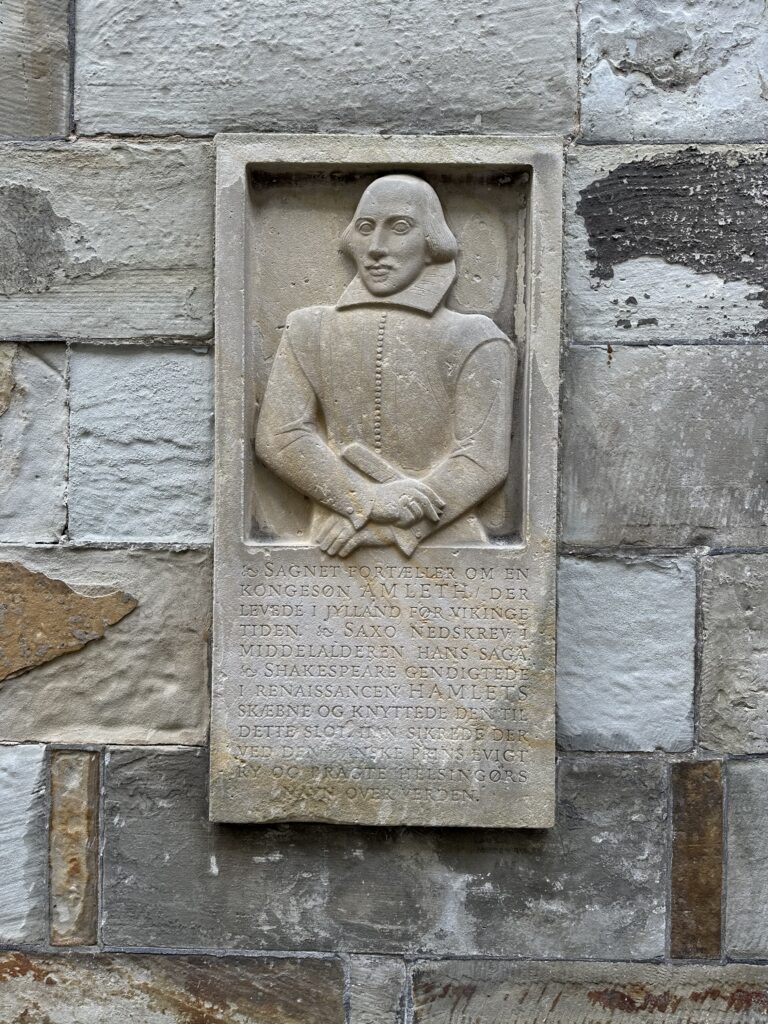

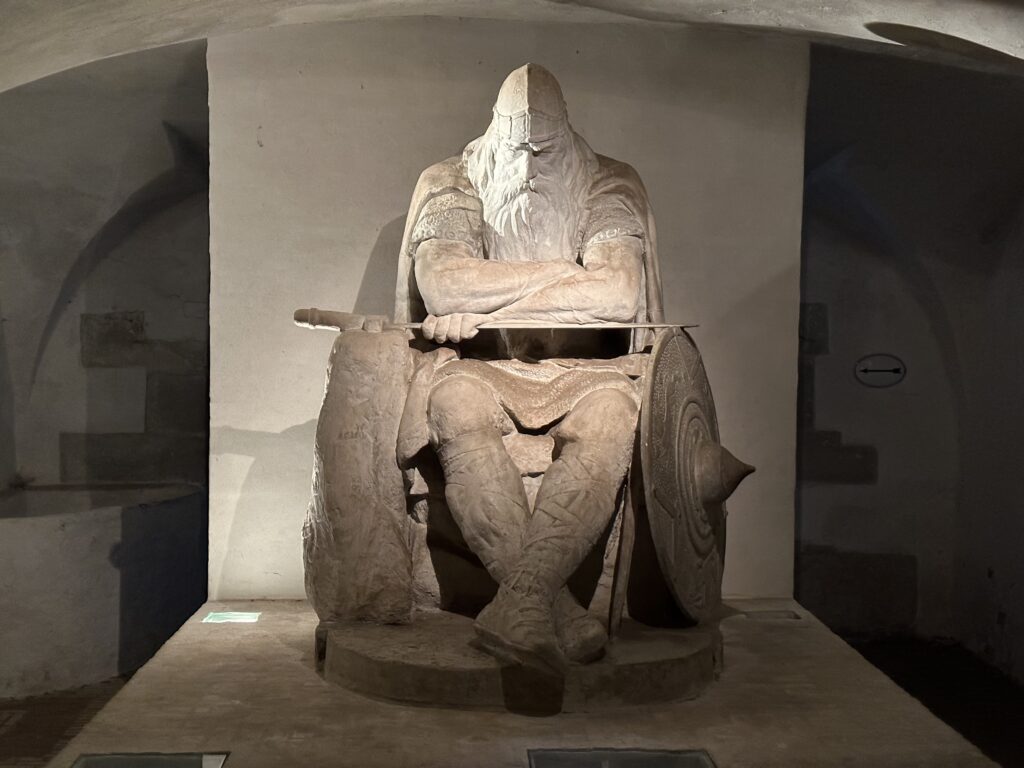

Later we took a guided drive along the coast of the Danish Riviera, a string of wealthy towns leading to Kronborg castle, the setting for Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.’’ The castle has gloomy underground tunnels and rooms called casemates that once housed soldiers and their horses. Now the only resident is Holger the Dane, a statue of a sleeping warrior who will supposedly wake up to defend Denmark when the country is threatened.

We happened to visit on the day of the area’s annual Beer Run, when thousands of young people dressed like pirates, clowns and FBI agents walk along the coast to the grounds of the castle, where they get shitfaced and party like it’s New Year’s Eve. When I waded into the crowd to take a video, I was bombarded with flying beer cans and encouraged to show off my dance moves, which peaked with the Twist in the early 1960s. Nearby, I saw a few inebriated gentlemen pissing into the moat surrounding the castle. (I’m pretty sure that scene wasn’t in “Hamlet.’’)

Our next flight took us to Bergen, a charming waterfront city on the west coast of Norway. While walking around town, we stopped at a bar to ask for directions and met a young couple from London. The wife grew up not far from me in suburban Philadelphia, the latest of many improbable local connections we’ve made while traveling around the world. (We met a woman in New Zealand who knew one of Pat’s sisters and ran into an elderly lady in Slovakia who lived a few miles from us in New Jersey.)

Bergen’s best-known section is Bryggen, which became one of Northern Europe’s leading trading centers in the 14th century. A row of wooden buildings with colorful facades line the eastern side of Vagen harbor, replicas of structures destroyed by numerous fires over the years. Today, warehouses that once housed fish and grain have been converted into restaurants, pubs, shops and museums. Bryggen is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site where 61 of the oldest buildings are being meticulously restored.

Bergen is a hub for Norwegian artists, and we were in town during the city’s annual international arts festival. (Bergen’s renowned concert hall is shaped like a grand piano.) We saw a terrific free concert in the town square by Sei Selina, a sultry young Norwegian singer with African roots who mixes musical genres and grew up listening to Aretha Franklin and Nina Simone. Not a bad pair to emulate.

A popular activity in Bergen is riding the funicular up to a large park that overlooks the city. On the way up we saw upscale homes scattered along the hillside; at the top we watched goats graze in a field and kindergarten students frolic in a playground.

The following day we did the “Norway in a Nutshell’’ trip across the country to Oslo, a popular all-day adventure that involves trains, buses and boats with picturesque views of Norway’s countryside. One memorable stop was at the Stalheim Hotel, whose terrace offers a breathtaking view of the Naeroy Valley about 85 miles northeast of Bergen. A short distance away is the tiny village of Flam, where we rode a train on one of the steepest railways in the world, carrying us 12 miles up to a remote mountain station that connected us to the train to Oslo.

Norway’s capital was under heavy security because of a NATO meeting of foreign ministers, causing major traffic jams in the city. But we did manage to visit excellent museums highlighting the careers of two famous Norwegians, explorer Thor Heyerdal and painter Edvard Munch.

The Kon-Tiki Museum tells the story of Heyerdahl’s legendary 1947 journey aboard a hand-built, wooden raft from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands in the South Pacific. Heyderdal and his five-man crew made the 101-day, 5,000-mile voyage in an attempt to support his theory that Polynesia was first settled by South Americans who sailed there in primitive rafts. The expedition led to a best-selling book by Heyerdahl and an Oscar-winning documentary. The original Kon-Tiki raft, named after an Inca god, is on display at the museum.

The ultramodern Munch Museum houses 28,000 artworks, including eight versions of the artist’s most famous work, “The Scream,’’ which depicts an androgynous person with a skull-shaped head, elongated hands and hollow eyes standing on a bridge with hands cupped over the ears and a horrified look on the face. The museum alternates displays of three versions (an 1893 drawing, an 1895 print and a 1910 painting) to avoid overexposure to light that could damage the works, which were made on fragile cardboard or paper. Maybe also to confuse potential thieves, given that versions of “The Scream’’ have twice been stolen from Oslo museums.

Frogner, the city’s largest park, showcases the work of Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland. It contains 212 of Vigeland’s bronze and granite sculptures, illustrating the human life cycle from childhood to death. Fifty-eight of the figures line a long bridge leading to a huge fountain with a centerpiece showing six muscular men holding up a giant bowl of cascading water. Then you pass through a wrought-iron gate and climb up several dozen circular steps to the Monolith, a 46-foot tall, phallic-shaped tower carved from a single block of stone and engraved with 121 naked, intertwined human figures.

Lots of children and teenagers were in the park the day we visited. If this were Alabama or Florida, their parents probably would have been arrested for corrupting the morals of a minor.

On our last night in Oslo, we ate dinner outdoors at a pier restaurant. We ordered the house specialty, a massive seafood platter for two with shrimp, crab, mussels and scallops. Unfortunately, we misread the price on the menu and ended up getting stuck with a $250 tab. The food was delicious, but not THAT delicious.

The next day we took an eight-hour, high-speed train to Stockholm, where we stayed at a boutique hotel owned by Benny Andersson of the Swedish supergroup ABBA.

The city stretches across 14 islands connected by bridges and ferries. One of the islands, Djurgarden, contains a cluster of museums, including ones dedicated to shipwrecks, art, Vikings, ABBA and alcoholic drinks. But the main attraction is the Vasa Museum, which contains the only 17th-century ship that has ever been salvaged almost fully intact.

The Vasa was a 64-gun warship that sank in Stockholm harbor on her maiden voyage in 1628. The 226-foot long ship, made of oak and decorated with hundreds of ornate wood carvings, was pulled from the water in 1961 and restored to its original glory. So why did it capsize and sink? Basically, because it was too tall and too narrow, making it unstable when struck by strong winds on its first voyage. An investigation was held into the sinking, but no one was held responsible because the ship was a pet project of Sweden’s king at the time, Gustavus Adolphus.

We had a hard time getting around the city that day because many streets were blocked off for the Stockholm Marathon. However, we did make it to the Olympic Stadium around dinnertime to watch the slowest runners cross the finish line as their family and friends cheered wildly from the stands. (Pat and I did our own half-marathon that day, walking 12 miles around the city with a rest stop at the Royal Opera House, where we watched a wedding reception near the front steps.)

Incidentally, the brick stadium was where Jim Thorpe won the decathlon and pentathlon at the 1912 Olympics, gold medals that were later rescinded because he supposedly violated an amateur requirement by previously playing professional baseball. The medals were posthumously returned in 1982, a tacit admission that the amateur rule was always a crock.

One day we did a guided country tour that started with a trip to Drottningholm, a royal palace outside Stockholm with lush gardens, a theater and a Chinese Pavilion. Our guide told us a story about two Israeli tourists who were arrested for entering a private garden at the palace. The women were released at our guide’s urging, though they were sent back to their cruise ship and banned from entering Sweden again. Don’t mess with Swedish royalty!

Our driver, a young man who once played junior hockey in Alaska, told us some funny stories about celebrities that he and his limo company have chauffeured around Stockholm. He said when Beyonce came to town last month, she and her entourage brought along 150 suitcases and bags — just 148 more than Pat and I combined.

Our next stop was Sigtuna, the oldest town in Sweden. Founded in 970 A.D. during the Viking Age, it’s now a quaint tourist destination with a 13th-century brick church and the ruins of several ancient stone churches. It also has an 89-seat movie theater called Grona Laden that’s been around since 1929. The walls are decorated with old movie posters and pictures of Golden Age Hollywood stars such as John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart and Clark Gable, but the theater stays up to date by showing first-run films like the new “Little Mermaid.’’

The manager told us that Grona Ladan used to share film reels with a bigger theater in another town. After the first reel was shown in one theater, it would be sent to the other theater so they could both show the same movie on the same day. Younger readers, be sure to Google what a film reel was.

On our last full day in Stockholm, we saw a huge private yacht with a helicopter perched on top docked in the harbor. When I asked a middle-aged man standing nearby whose yacht it was, he said it belonged to an unidentified Microsoft bigwig. (After returning home, I learned that the new $250 million superyacht belongs to former Microsoft executive Charles Simonyi, the brainchild behind the company’s Office software. Along with an outdoor movie theater, the yacht reportedly has a pool that can be converted to a dance floor.)

We later saw a military marching band walking to the city’s Royal Palace for the changing of the guards ceremony. That’s the palace where official business is conducted, as opposed to Drottningholm, where the royals actually live. Kings and queens can never have too many palaces.

Our last stop was a photography museum housed in a former ship terminal. The featured exhibit was called “Santa Barbara,’’ which chronicled the journey of a young Russian mother and her two children to the U.S. in 1996. Desperate to leave Russia, the mother answered an ad for a mail-order bride and ended up unhappily married to a fat old guy in California. Her daughter became a photographer and has recreated her family’s wrenching immigrant experience with pictures and film using actors playing her mother, herself and her brother.

By the way, Fotografiska advertises itself as the “world’s most open museum’’ because it’s open every day from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. So no excuses not to visit.

We then took an overnight ferry from Stockholm to Helsinki, Finland. They call it a ferry, but it’s more like a cruise ship, complete with restaurants, bars, shops, a casino, a theater, saunas, hot tubs and cabins. En route we passed through the Stockholm archipelago, a cluster of 30,000 islands (some inhabited) in the Baltic sea that are only accessible from the mainland via ferry or private boat.

Shortly after arriving, we did a walking tour of the Finnish capital that included a stop at the city’s futuristic central library. Called Oodi, it has book-sorting robots, game rooms, a movie theater, a restaurant, recording studios, 3D printers and concert venues. The spacious top floor, dubbed “book heaven,’’ has floor-to-ceiling windows and is illuminated by circular roof lights. There are comfortable seats everywhere in the building, making it a social and cultural center as well as a mecca for bookworms. Quite a contrast to the U.S., where libraries are constantly downsizing and cutting hours.

We also saw the city’s glass concert hall and Temppeliaukio Church, known as the Church in the Rock because it was carved directly into a granite cliff. Covered by a copper dome, the church has crystal-clear acoustics and is often used for classical music concerts. The day we visited, a German pianist was playing some of his own compositions.

While walking through a popular outdoor market, we bought some vendace, a small sardine-like fish served like french fries in a paper tray. Our guide warned us to be wary of the lurking seagulls, who like to swoop down and steal the fish. Sure enough, seconds later, a seagull dive-bombed our tray and scooped up a quick snack, leaving the leftovers on the ground.

Our final stop of the day was at the Ateneum art museum, which featured a major exhibit of Finnish painter Albert Edelfelt, who spent much of his life in Paris. I’m more history buff than art expert, so I was interested in how Edelfelt traveled around Europe so widely in the late 1800s at a time when that wasn’t so common. I counted at least a dozen countries he visited or lived in during his adult life — all without accumulating any frequent flyer miles.

We ended our trip with a quick visit to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, just a two-hour ferry ride from Helsinki across the Gulf of Finland. The Old Town section, filled with cobblestone streets, Gothic spires and restored warehouses converted into shops and restaurants, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the best preserved medieval cities in Europe.

Next to the Estonian History Museum, signs condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hung from a temporary barricade. Some of the English-language signs read: “Putin is a child abductor,’’ “Stop War Criminals’’ and “Fascism will not be forgiven.’’ Though Estonia is a member of NATO, Tallinn is only 130 miles from the Russian border, so Estonians have a legitimate fear of their aggressive superpower neighbor.

We ate lunch at a sidewalk cafe where the manager, a Spaniard who married an Estonian woman, asked where we were from. When I said “New Jersey,’’ he smiled and started reeling off names of famous entertainers from the Garden State: Bruce Springsteen, Jack Nicholson, Bruce Willis, Frank Sinatra, John Travolta.

Small world, indeed.

Hi Rick! I love reading about your travels, and this one was especially interesting because I don’t know anyone who has traveled to these countries, let alone take wonderful photos and tell stories about people, places, and experiences!

Hi Rick,

As always, I love reading about your travels!!! You describe these places in such an inviting way. I wish I could get on a plane right now and see what you saw.

I look forward to the next one!!

Hi Rick,

As always, your descriptions bring these countries to life and make me want to visit them too!! I can’t wait for your next trip!!

Rick, I love reading about the adventures you and Pat take. Beautiful photos and wonderful descriptions! Where to next?

Another tour-de-force travelog, Rick. We went to some of the same places, and it brought back fond memories. Keep traveling and writing!

Rick, Pat, great to meet both of you as in part of this trip.

I was waiting for your post, Rick! I always love reading about your adventures, and now, I am enthralled with the Nordic countries…and totally exhausted at the pace of your travel. Thank you for keeping us all up to date with your travels!

Rick! As usual, a stupendous report with delicious pictures. Some of your trip were locations where we’d intended to visit in 2021 which of course didn’t happen. Some were historic places that meant a lot to me — such as finishing my 100th marathon in Stockholm on their 100th anniversary of their Olympics. Thank you so much for your great commentary, introduction to new areas, and fond membranes of places once visited. Keep going! We need you! Fondly, Diana