You can’t see Russia from Sarah Palin’s house, but you can see lots of other amazing things in Alaska.

From fierce grizzly bears, giant moose and speedy sled dogs to glistening glaciers, towering Sitka spruce trees and the tallest mountain in North America, the 49th and largest state offers visitors a cornucopia of natural wonders rarely seen in the Lower 48.

On a recent trip to Alaska that included a cruise along the state’s southeast coast and a visit to Denali National Park, my wife Pat and I discovered why so many adventurous, independent people are drawn to a remote, frigid place that was part of Russia until 1867 and didn’t become a state until 1959.

After flying from Newark to Vancouver, we boarded a Silversea cruise ship for our seven-day voyage through the Inside Passage, which weaves between islands along the western coast of Canada and the southeast shore of Alaska.

The route is dotted with tiny tourist towns that cater to cruise passengers who leave their ships for land excursions that include biking, hiking, rafting, kayaking, glacier walks and visits to sled-dog training camps. More sedentary folks can spend their time ashore browsing at the endless array of souvenir shops, art galleries, jewelry stores, restaurants and bars that are the lifeblood of these coastal communities.

While I’ve traveled extensively around the world, this was only my second cruise — and I only did it because it was a special celebration with seven members of Pat’s family. I’ve never been a fan of the cruise lifestyle, which typically features passengers gorging on food, getting drunk and watching second-rate shows. However, if you want to see Alaska’s southeast coast, the thin strip of territory that runs about halfway to Vancouver along the border with British Columbia, cruising is the most practical way to do it.

Fortunately, we didn’t travel on one of those mega-ships crammed with thousands of passengers; ours only carried 260, about 100 fewer than capacity, making it comfortable and convenient to move around. Each cabin also came with its own butler and “suite attendant,’’ which made me feel like I was the lord of some royal palace instead of a retired journalist from New Jersey.

It took about 40 hours for the ship to travel from Vancouver to Ketchikan, Alaska, our first stop along the Inside Passage. Today, it’s a typical southeast coastal town geared toward tourists, but in the 1920s Ketchikan was known as “Uncle Sam’s Wickedest City’’ for its infamous red-light district filled with whorehouses, speakeasies and gambling parlors whose main clientele were fishermen seeking a good time during work breaks.

Creek Street has now been transformed into a shopping mecca with a quaint boardwalk. However, reminders of its sordid past still remain, including a street sign reading “Married Man’s Trail,’’ once a muddy path through the woods that pleasure-seeking men used to discreetly visit the sporting ladies of Ketchikan.

During our stop, Pat and I paddled a two-person kayak around the Tatoosh Islands, where we spotted dozens of bald eagles easily identifiable by their snowy white heads. The islands are part of Tongass National Forest, which covers almost 17 million acres, making it the the largest U.S. national forest and the biggest intact temperate rain forest in the world.

The following morning we docked in Juneau, the only state capital in the U.S. that isn’t accessible by road. The city isn’t on an island, but the surrounding terrain of icefields and glaciers have made it impractical to build an access road. (Living in the most densely populated state in the U.S., where traffic jams are a daily headache, I almost wish we were that isolated.)

Juneau is the largest state capital by area (2,700 square miles of land), but one of the smallest by population (32,000). It doesn’t take long to walk around the entire downtown, including a steep climb up to the capitol building, a domeless, brick and limestone structure that looks more like an office building than the home of state government.

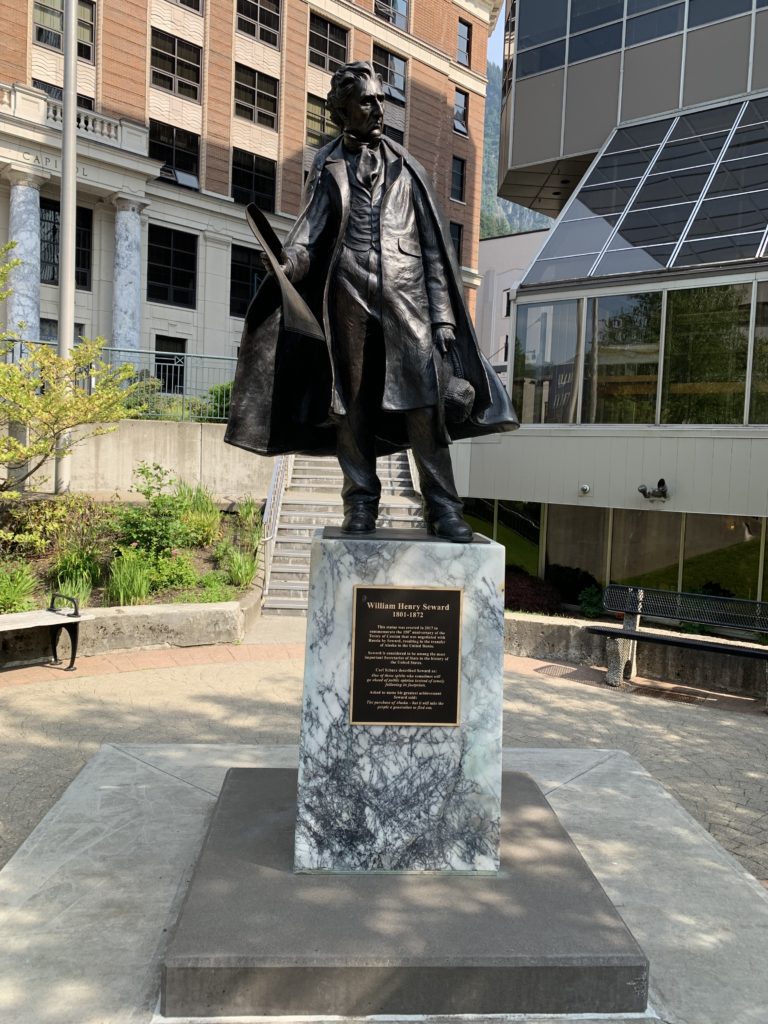

The plaza in front of the capitol has a statue of William Seward, who as U.S. Secretary of State negotiated the $7.2 million purchase of Alaska from Russia. Critics decried it as “Seward’s Folly,’’ but the discovery of gold in 1898 and the massive Prudhoe Bay Oil Field in 1968 have cast a more favorable economic light on the decision.

After visiting the first of three sled-dog training camps I saw during the trip (more on that later), our whole family group crossed over scenic Mendenhall Lake in a large raft steered by one of the many young guides who work in Alaska during the summer before returning to school or working other seasonal jobs elsewhere in the U.S. or abroad. We got a partial view of the 13-mile long Mendenhall Glacier before doing some mild whitewater rafting down a river bordered by lush forests and snow-capped mountains.

Like almost every day on our cruise, it was unusually warm and dry for Alaska. Global warming is readily apparent in the state, where glaciers are melting at an alarming rate and animals are being forced to adapt to a changing climate. Humans also must adjust. I brought one small tube of suntan lotion, thinking that would be plenty, and used it all up before we left the ship.

Our next stop was supposed to be Skagway, but the port was closed because of a recent landslide, so we docked at nearby Haines instead. I’m glad we did because Haines was my favorite town on the Inside Passage, the least touristy with the most homey feel. It’s the site of an old military fort built in the early 1900s that was used as a training base during World War I and World War II. One of the buildings is now a community theater; another is an Indian arts center. For those fascinated by tools, the town also has a museum that chronicles human history through the use of hammers.

While walking through Haines on July Fourth, we passed through a field where local residents were celebrating with children’s races, food stalls selling hot dogs and cotton candy, and dogs chasing Frisbees. We stopped at a small coffee/ice cream shop off the beaten track and met the owner, a senior citizen who moved to Haines with her husband from San Diego.

“We love it here,’’ she said, beaming with enthusiasm. “It’s an outdoor paradise.’’

Later, we rode on a motor boat along Alaska’s deepest fjord, passing a colony of sea lions beached on the rocky shore. One of them had a bloody tail, possibly from fighting with another male, but our pilot — who told me he spends his offseasons leading anti-poaching squads in Africa — said the wound would probably heal and the eared seal would return to the sea.

Upon arrival at Glacier Point, we boarded a bus that took us to a trailhead where we began a short walk over the moraine toward Davidson Lake. After getting outfitted with rubber boots and life jackets, we hopped on a 31-foot long canoe and paddled our way to the face of Davidson Glacier, where even amateur iPhone photographers can take pictures worthy of National Geographic.

The next day, after docking at Sitka, we took a four-mile bicycle ride on a winding coastal road, followed by short hike through the Tongass National Forest, where we saw slimy, crawling creatures known as banana slugs. On the ride back we stopped at Whale Park, where we gazed at a sculpture of a giant whale’s tail protruding from the ground but alas, saw no real Moby Dicks.

The following morning, we awoke to the massive site of Hubbard Glacier, which is 76 miles long, seven miles wide and as tall as a 30-story building above the waterline. It was only four miles away from our ship, but looked much closer.

The water in front of the glacier was dotted with icebergs that had broken off from the glacier. The icebergs, which are mostly submerged, are deceptively dangerous, as demonstrated 11 days earlier when the Norwegian Sun collided with one, damaging the ship and forcing an abrupt end to the cruise. (Incidentally, the Hubbard is one of the few glaciers in the world that is continuing to grow, rather than recede.)

While food, drink and spa treatments were the focus of many people on the ship, I was more interested in a series of lectures delivered by Niki Sepsas, a globetrotting Alabaman who presented slideshows on Alaskan wildlife, the Klondike Gold Rush and the state’s mighty glaciers.

Sepsas is an energetic septuagenerian who fell in love with Alaska in the 1970s while helping build the highway needed to support construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. He’s spent his adult life traveling the world (about 120 countries), and talking and writing about his experiences.

“I didn’t get married until I was 70 because I didn’t have the time,’’ he joked.

Our final stop on the cruise was Seward, located on the Kenai Peninsula about 130 miles south of Anchorage. From there, we rode a train northward to Girdwood, a resort town where we stayed overnight at a hotel before taking an all-day bus ride to Denali National Park.

Along the way, we stopped at Happy Trails Kennels, a sled-dog training center run by four-time Iditarod champion Martin Buser. Buser relies on the tourist trade to fund his dog training, and we contributed our small share by buying a couple of branded T-shirts at the gift shop.

The visit included a film about the Iditarod, the world’s most famous sled-dog race, which covers more than 1,000 miles from Anchorage to Nome in freezing temperatures that have dipped as low as minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit. We also saw a brief demonstration of five dogs pulling a four-wheeler driven by Buser. (At the first training camp I visited, I actually got to ride in a wheeled cart pulled by 12 dogs.)

Sled dogs, by the way, are Alaskan Huskies, which are smaller, faster, longer limbed and less hairy than the more popular Siberian Huskies. They are bred for speed and endurance, two traits essential for the exhausting Iditarod and other long-distance races. From what I saw and read, most centers give these dogs excellent care, providing plenty of rest and playtime when they aren’t going on training runs.

Each Husky had its own wooden doghouse, and many of them were standing or lying on the flat roofs of their homes while we visited. We got to pet many of the dogs, who were very friendly, and even were allowed to hold some adorable jet-black puppies. For a nutty dog lover like me, it was as exciting as viewing the Hubbard Glacier.

About two hours from the entrance to Denali National Park, we stopped at McKinley View Lodge, where on a clear day you can get a splendid view of Mount Denali, which at 20,310 feet is the tallest mountain in North America. Luckily for us, it was a clear day, so we gained entrance to the “30 Percent Club,’’ which is what your chances are of seeing the famous mountain that is usually covered by clouds.

If Mount Denali doesn’t ring a bell, it’s because it was called Mount McKinley (a gold prospector named it after then-presidential candidate William McKinley in 1896) until it was changed back to its native name in 2015.

After staying overnight at a hilltop lodge just outside the park entrance, we boarded a bus the following morning for a five-hour guided tour of what is now officially known as Denali National Park and Preserve, which was tripled in size to about six million acres in 1980.

Everyone who visits Denali hopes to see at least a few of the “Big Five’’ animals that live in the park: grizzly bears, moose, Dall sheep, caribou and wolves. The truth is, given the huge size of the park and the relative scarcity of those animals, your chances of seeing most of them in one or two days are slim. (The combined population of the five animals is an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 in an area roughly the size of Vermont.)

During our tour, the only Big Five animals we saw were Dall sheep, and you needed binoculars to spot them near the top of a mountain. Adult males (rams) have huge, curly horns, while the females (ewes) have smaller, slender ones. I think we saw a mix of rams and ewes, but it was hard to tell from such a great distance.

However, we did get a roadside glimpse of a cute Arctic ground squirrel, who stood up on his hind legs and looked like he was begging for food.

After returning to our hotel, our niece Liz joined Pat and I for a quick visit to the strip of shops and eateries on a boardwalk at the bottom of the hill. We bought tasty pizza and ice cream at Miller’s Gourmet Popcorn, which was once named the best restaurant in Denali even though it’s really a takeout joint. Glancing at my bulging belly, I resisted the urge to buy the house specialty, McKinley Munch popcorn, described as a “Mountain of Flavor’’ containing caramel, white and dark chocolate, and roasted nuts.

Before leaving the park, it’s worth stopping at the Denali Visitor Center, which features exhibits on the history of the park and the animals that live there. You can also watch films on the seasons of the park and the “freight dogs’’ that transport equipment and supplies during the winter when motorized vehicles are banned. (I got my third canine fix of the trip by visiting the training camp for the freight dogs, who are larger and have a heavier coat than the racing dogs.)

Finally, it was time to head home. The first leg of our trip to Anchorage was aboard the Wilderness Express, a luxury, glass-domed train that took us to Talkeetna, where we boarded a bus for the two-hour trip to the state’s largest city.

Riding the Wilderness Express was a throwback to the heyday of first-class train travel, with plush roomy seats, fine dining and spectacular views of the Alaskan countryside. During one roadless, 65-mile stretch, local residents can flag down the train by waving their hands or displaying a bright object. The conductor will stop the train and give the locals a lift to a town or city where they can buy food and equipment, send mail or visit friends.

One of the stranger sights we saw from the train window was a turquoise building with a V-shaped roof and a hand-lettered sign on the front reading “Sherman City Hall.’’ It’s the home of Clyde and Mary Lovel, who bought the homestead house in 1964 and raised four children there while Clyde worked for the railroad and Mary wrote two books about living in the wilderness. One day, while the Lovels were out of town, Clyde’s visiting brother-in-law painted “Sherman City Hall’’ above the two ground-floor windows and the humorous sign has remained ever since. The Lovels still own the home, but now only live there in the summer.

In Anchorage, we ate on the popular rooftop patio at 49th State Brewery overlooking Cook Inlet and stopped at a small shop owned by native Alaskan women that sells scarves, caps and other items handmade from musk ox wool, which is billed as the softest, warmest natural fiber in the world. It’s also one of the most expensive. One of the ski caps cost $295, and scarves ranged in price from $295 to $395. Pat settled for a $25 musk ox bracelet.

Our trip ended on a slight down note when Pat and I, along with two of Pat’s three sisters and a brother-in-law, got sick just before or right after flying home from Anchorage. We all ended up testing positive for COVID, though we were more fortunate than our niece who got the virus early in the cruise and had to spend the rest of her time at sea isolated in a locked room below deck with only a small window to peer out at the gorgeous scenery.

Thankfully, we all recovered quickly, leaving us with nothing but fond memories of Alaska.

Rick! Wonderfully well written and it was as near as could be to feeling like I was there. I’d only been to Kenai, Anchorage and Denali. You sure did well, and even better to tell the stories so interestingly. So many new places for me, and new observations. You only missed the sisters gathering at the bar for shots of Duck Fart (Kahlua, Baileys and Whiskey). Hahaha. It looked so fun. All of the trip was fun and educational. Thanks for sharing. Diana