Long before I became a sportswriter, I saw many remarkable games and legendary athletes as a fan growing up near Philadelphia in the 1960s. Here are some of the most memorable ones, in chronological order:

EAGLES WIN NFL CHAMPIONSHIP, 1960

The game took place Dec. 26, 1960 at Franklin Field on the University of Pennsylvania campus in Philadelphia. It was held on Monday instead of Sunday because, hard as it is to believe today, the NFL had this quaint notion that football shouldn’t be played on Christmas. There also was an unusually early kickoff (at noon) because Franklin Field had no lights and the NFL was worried that another overtime game, like the famous Giants-Colts matchup two years earlier, might drag past dusk.

A capacity crowd of 67,325, including 7,000 in temporary bleacher seats, packed the stadium for the showdown between the Eastern Division champion Eagles (10-2) and the Western champion Packers (8-4). It was a crisp, clear day with a kickoff temperature of 48 degrees, but after a week of frigid weather the field was still ringed with patches of snow left over from a storm several days earlier.

My dad and I sat in the upper deck above the 30-yard line. I remember borrowing a pair of binoculars from a man sitting next to us so I could get a clearer look at the players who, while small by today’s standards, seemed like giants to me then. I especially wanted to get a close-up of my favorite Eagles — crafty veteran quarterback Norm Van Brocklin, bantam receiver Tommy McDonald and ferocious lineman Chuck Bednarik, the last of the NFL’s “60-Minute Men’’ who played regularly on offense and defense.

Philadelphia was coached by Buck Shaw, a former Notre Dame star under Knute Rockne who had taken over a moribund Eagles team in 1958 and quickly turned them into a championship contender. Packers coach Vince Lombardi had pulled off a similar turnaround in Green Bay after taking over in 1959 following the worst season in franchise history. Both teams were trying to return to their glory days – the Eagles had won consecutive NFL titles in 1948-49, while the Packers had captured five championships during a decade of dominance from 1929-1939.

After Philadelphia took a 17-13 lead on a 5-yard touchdown run by rookie Ted Dean with 5:21 left, the Packers drove deep into Eagles territory in the closing minute. On the final play, quarterback Bart Starr threw a short pass to fullback Jim Taylor, who broke a tackle and reached the Eagles’ 9-yard line before being stopped by Bednarik and defensive back Bobby Jackson. Bednarik sat on Taylor and refused to let him get up until the final seconds had ticked off. Then Bednarik growled, “You can get up now, Jim, this (expletive) game is over.’’

The game was noteworthy on several counts. First, it was the only playoff game Lombardi ever lost. He would go on to lead the Packers to five NFL championships over the next seven years, including victories in the first two Super Bowls. Also, it started a 57-year championship drought for the Eagles, which didn’t end until they won the 2018 Super Bowl.

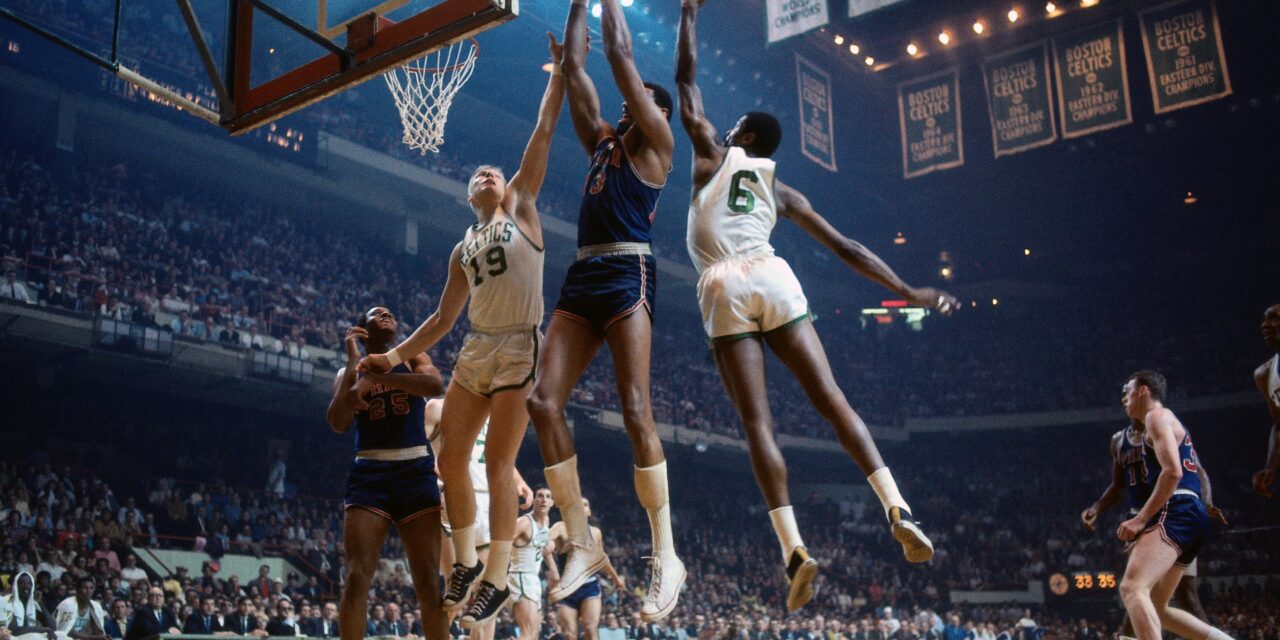

WILT CHAMBERLAIN DOMINATES BILL RUSSELL, 1961

Wilt Chamberlain was already a legend when I first saw him play on Saturday, Dec. 30, 1961 at musty Convention Hall in Philadelphia. Only 25 years old, the giant Philadelphia native was en route to a historic NBA season in which he averaged 50 points a game, including a record 100-point explosion against the New York Knicks in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Playing for his hometown Warriors against Bill Russell’s archrival Boston Celtics, Chamberlain scored 41 points and grabbed 28 rebounds in an overtime loss to the Celtics as I watched from a balcony seat. Chamberlain completely outplayed Russell, holding him to 11 points, but his team still lost — a pattern that plagued him his entire career.

I still remember passing him in a corridor before the game as he made his way to the locker room. He was the most physically imposing human being I’d ever seen — 7-feet, 1-inch tall and 270 or so pounds of lean muscle, with racehorse legs and hands the size of dinner plates.

In addition to being a basketball Hall of Famer, Chamberlain was a track and field star in college and a superb volleyball player. He’s certainly one of the greatest all-around athletes in history and, in my opinion, the most dominant basketball player of all time.

TERRY BAKER’S 99-YARD TD WINS LIBERTY BOWL, 1962

The game, played on Saturday, Dec. 15, 1962 at Philadelphia Municipal Stadium (later renamed John F. Kennedy Stadium), pitted local team Villanova against Oregon State, led by Heisman Trophy winner Terry Baker.

It was played on a frozen field with temperatures in the low 20s before a sparse crowd of 17,048 at a stadium that seated 100,000. I remember hiding out in a bathroom at halftime in a vain attempt to get warm and regain feeling in my numb hands.

Neither team was a college football power, but Oregon State was a heavy favorite because it entered the game on a six-game winning streak, including a victory over then-undefeated West Virginia.

Because of the slippery field, it was hard for either team to generate much offense. The only score came in the first quarter on a 99-yard run by quarterback Baker, who eluded a tackler in his own end zone and raced down the left sideline for a touchdown. The Beavers failed on a two-point conversion and the 6-0 score held up after a Villanova touchdown was negated by a penalty.

Baker, incidentally, was also a guard on the Oregon State basketball team that lost in the 1963 national semifinals to two-time defending champion Cincinnati. To this day, he’s the only college athlete to win football’s Heisman Trophy and play in basketball’s Final Four.

ARMY-NAVY GAME ENDS IN CONTROVERSY, 1963

In a game postponed a week following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, his beloved Navy beat Army 21-15 in a strange finish to the annual showdown between the two military schools.

I can’t recall where I sat among the sellout crowd of 102,000 at Municipal Stadium on that Pearl Harbor Day — Saturday, Dec. 7, 1963 — but I do remember the somber atmosphere at the start of the game, which began with a moment of silence in memory of the late president who was a Naval officer in World War II. All the flags at the stadium were at half mast and the presidential box where JFK sat the previous year was filled with black flowers.

(Military officials considered canceling the game, but Jackie Kennedy insisted her husband would have wanted it to be played.)

What I do remember clearly is the bizarre end of the game, which matched the second-ranked Midshipmen (8-1) against a strong Army squad (7-2) that had shut out four opponents and upset Penn State on the road. The stakes were even higher than usual since the winner was set to meet top-ranked Texas in the Cotton Bowl.

Army did a stellar job containing Roger Staubach, Navy’s Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback, but fullback Pat Donnelly’s third touchdown of the day gave the Midshipmen a 21-7 lead early in the fourth quarter. However, Army rallied behind quarterback Rollie Stichweh, whose touchdown and two-point conversion cut Navy’s lead to six points with about six minutes left. (CBS immediately showed his touchdown again, marking the first use of instant replay.)

Stichweh then recovered an onside kick and drove Army to the Navy 2-yard line in the closing seconds. But, unaware that the clock had restarted following a short stoppage by the officials, Stichweh was unable to get off another play, leaving players on both sides stunned by the abrupt ending.

SANDY KOUFAX’S NO-HITTER AGAINST PHILLIES, 1964

While the Philadelphia Phillies were my favorite boyhood team, my favorite pitcher was Sandy Koufax of the Los Angeles Dodgers. So whenever Koufax pitched in Philadelphia, I tried to attend the game at old Connie Mack Stadium.

On Thursday, June 4, 1964, I sat behind home plate when the first-place Phillies met the eighth-place Dodgers, featuring a marquee pitching matchup between ace left-handers Koufax and Chris Short.

The game was scoreless until the seventh, when Dodgers slugger Frank Howard crushed a three-run homer that landed on the roof in left field.

Meanwhile, Koufax was unhittable with his blazing fastball and swerving curveball. He walked Dick Allen on a full-count in the fourth inning, but Allen was caught trying to steal second and nobody else reached base for the Phillies. When Koufax struck out pinch-hitter Bobby Wine to end the game, it gave the Dodgers pitcher the third of his four career no-hitters. He faced the minimum 27 batters, a feat he would match the following year when he pitched a perfect game against the Chicago Cubs.

Don Drysdale, L.A.’s other star pitcher, wasn’t at the game after losing the previous night 1-0 in 11 innings. When he heard that Koufax had pitched a no-hitter for the weak-hitting Dodgers, he asked, “But did he win?’’

MICKEY MANTLE’S WALK-OFF SERIES HOMER, 1964

On Saturday, Oct. 10, 1964, my uncle Lew took me and my cousin Kenny to Game 3 of the World Series between the New York Yankees and St. Louis Cardinals at Yankee Stadium.

We sat parallel to third base, about a dozen rows back, in the sellout crowd of 67,101 at the House That Ruth Built. The Series was tied 1-1, so this was a pivotal game matching the aging Yankees dynasty against the upstart National League champs.

It turned into a pitcher’s duel between Cardinals veteran Curt Simmons and the Yankees’ hard-throwing Jim Bouton, who later co-wrote the best-selling book “Ball Four.’’

Throughout the game, my uncle kept making preposterous predictions about what would happen on the field, leading to a series of losing bets. By the ninth inning, he owed me $50, which to a 12-year-old seemed like a million bucks. When Mickey Mantle led off the bottom of the ninth with the Yankees and Cardinals tied 1-1, Lew bet me double or nothing that Mick would win the game with a first-pitch homer into the upper deck in right field. I immediately agreed, knowing that the odds of that happening were astronomical.

Sure enough, Mantle took a mighty swing at the first pitch from knuckleballer Barney Schultz and blasted the ball to the exact spot Lew had predicted, breaking Babe Ruth’s record with his 16th World Series homer. As Mantle rounded the bases, I looked at my uncle with awe. Knowing I felt crushed about losing the bet, Lew gave me the $50 anyway.

Footnote: I should have seen a World Series game in Philadelphia that year, but the Phillies blew the National League pennant by squandering a 6 1/2-game lead with 12 games left. They lost 10 straight down the stretch, beginning with a 1-0 loss to Cincinnati when Chico Ruiz stole home. The Phils regrouped to win their final two games, but still ended up one game behind the pennant-winning Cardinals. The team started selling World Series tickets before the collapse and my dad bought a pair for Game 1 at Connie Mack Stadium. Needless to say, they were never used. I’m sure those tickets would be worth a lot today, but unfortunately my mom threw them out along with my extensive baseball card collection when I went off to college. I still haven’t forgiven her.

NESHAMINY EXTENDS UNBEATEN STREAK VS. EASTON, 1965

My high school, Neshaminy in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, was a football powerhouse from the early 1950s to the early 1970s, producing future pro stars like Oakland Raiders lineman Harry Schuh and kicking brothers Chris and Matt Bahr, who each played on two Super Bowl champion teams.

From 1961-65, Neshaminy went 51 games without a loss, at the time one of the longest such streaks in high school history. One game during that streak stands out in my memory. It happened on Friday night, Sept. 24, 1965 against Easton High, another Pennsylvania football power. It was Game No. 43 during the unbeaten run and I was a 13-year-old packed into the sellout crowd of 10,000 at Heartbreak Ridge, the new nickname for Neshaminy’s field taken from a famous Korean War battle.

Easton led the entire game until the closing minutes, when Neshaminy’s star quarterback Jim Colbert faked a pass, dodged several tacklers and sprinted 61 yards for the go-ahead touchdown. Neshaminy’s defense then made a goal-line stand to seal the 33-27 victory.

Three decades later, when I was the national college football writer for The Associated Press, Colbert’s name came up while I was talking to Penn State coach Joe Paterno. Colbert was recruited by Paterno, though he ended up transferring to the University of Delaware.

Paterno had a photographic memory, and when I mentioned that I was a 1970 Neshaminy graduate, he immediately recalled watching Colbert’s dazzling dash against Easton on a highlight tape. “That was one of the greatest runs I ever saw by a high school player,” he said.

CALVIN MURPHY SETS PALESTRA SCORING RECORD, 1967

During the 1960s, I saw dozens of college basketball games at the Palestra, home court for the University of Pennsylvania and site of many thrilling intracity battles between Philadelphia’s top college teams.

However, one game I’ll never forget was a victory by a visiting team from the outskirts of Buffalo, New York.

I had a courtside view of little Calvin Murphy of Niagara University putting on one of the greatest basketball displays I’ve ever seen. Murphy, a 5-foot-9 sophomore, broke the Palestra scoring record with 52 points to lead Niagara to a 100-83 win over La Salle on Saturday, Dec. 16, 1967.

He scored every way possible, from acrobatic drives to long jumpers to breakaway layups. He was like a windup toy that never stopped moving, jumping over much taller players and scooting around and past anyone who tried to guard him, including La Salle’s excellent defensive guard Roland “Fatty’’ Taylor. Playing in only his fifth varsity game, Murphy got a long standing ovation from the opposing fans when he went to the bench in the final minute. “He’s the best shooter I’ve ever seen,’’ said La Salle coach Jim Harding.

Murphy was a three-time All-American who averaged 33 points a game at Niagara and went on to have a long, successful career in the NBA, where he made a then-record 78 free throws in a row. He also was a world-class baton twirler who performed at halftime of Buffalo Bills games when he was in college, and he has the distinction of being the shortest player in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Rick, I love reading these stories of sports events that have stayed with you!

Good ol’ Uncle Lew, what a big heart he had.

And Calvin Murphy, wow he went to Norwalk High when I was in the other public high school in Norwalk, CT (after moving away from Millburn).

Thanks for the memories.