School started today, and I felt like a little kid on his first day of kindergarten: excited, nervous and not sure what to expect.

Walking to the old campus, where I had to catch a bus to the new campus, I saw hundreds of blue-shirted youngsters (many Chinese grade-school students wear uniforms) on their way to school. In the courtyard of the old campus, an old man was doing tai chi with a sword as traditional Chinese music played in the background. With his graceful, slow-motion movements, he looked like a warrior performing a ballet.

I also saw first-year university students, dressed in fatigues, doing their compulsory physical training. All freshmen spend two weeks in September in a college version of basic training, although they’re not part of the military. They don’t start school until October, by which time they will theoretically be in top physical and mental condition for their classes. This is the opposite of U.S. college freshmen, who usually spend their last few weeks before school partying and getting drunk.

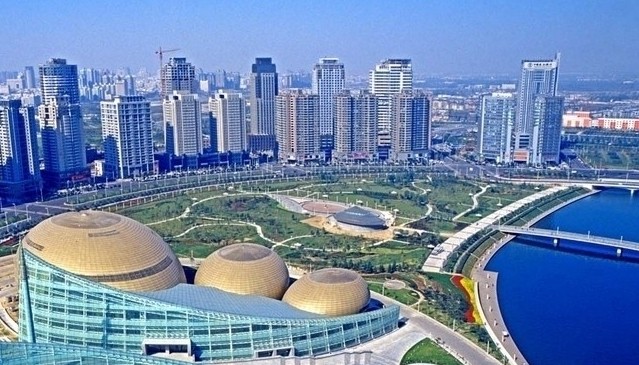

The bus ride to the new campus took more than hour, thanks to constant traffic jams exacerbated by construction detours and roadblocks. Everywhere you go, old roads are being torn up and new roads are being built. The dust from the construction sites makes the polluted air even worse, creating a dome of gray haze that covers the city.

I arrived on campus just 15 minutes before the start of my first class, at 8:30 a.m. I rushed to my office to meet Amber, our administrative assistant, who handed me my class roster and escorted me to my classroom in the building next door. Awaiting me were 22 students (13 males, nine females) seated at row-style blue desks.

I wrote my name on the blackboard and introduced myself by saying hello (pronounced knee how) in Chinese, one of about a dozen words and phrases that I’ve memorized using phonetic spelling. Then, in keeping with the English immersion theme of the class, I said, “That is the last word of Chinese you’re going to hear this semester.’’

The students laughed and my Chinese teaching career officially began. (All my classes this month are about writing. There are also speaking classes, but I’m not sure I’ll be teaching any of them.)

Each class is divided into two 45-minute sessions, separated by a five-minute break. I began by telling the students about my background as a journalist, my family and my reasons for coming to China. Then I asked each student to give me a brief bio, including their English and Chinese names, their hometowns, their families, their hobbies, etc.

To my surprise, more than half the students said they had at least one brother or sister. (The Chinese also call their first cousins brothers and sisters, but I told my students I only wanted to know about siblings from the same parents.) China has a one-child policy but, like most of the country’s rules, it can be broken if you pay somebody off. Amber told me that when she was born 26 years ago, her parents had to pay 8,000 yuan (about $1,300 in today’s dollars) because they already had a son. “I am an expensive child,’’ she joked.

When I asked the students about their interests outside class, the most common answers were movies, music and sports. A few mentioned reading, shopping and art. All but one student said they owned a computer.

As for career aspirations, several said teacher or translator. One wanted to be a farmer, another a clothing store owner. One girl said she wanted to make “a lot of money,’’ while another desired a “relaxing job’’ and a husband.

I told my students that I had traveled all around the world, including a safari in Africa last year. When I asked if anyone knew anything about Africa, one male student raised his hand and said, “black man.’’

During the second half of the class, I asked students to write about themselves so I could learn more about them and gauge their writing skills. I haven’t read the results yet, but a quick glance showed they have very good penmanship. (They all print because they aren’t taught cursive writing.)

After class, I met my boss, Richard Guo, a dapper, middle-aged Chinese man who lives in Toronto. Guo is the president and founder of Education in English, which has agreements with six Chinese universities (Henan University of Technology is the newest) to provide native English speakers as teachers. Richard spends a lot of time shuttling back and forth between Canada and China. I asked him what his wife thinks of his travel schedule. `Luckily, I am single,’’ he smiled.

After being treated to lunch in a school cafeteria by a Chinese teacher, I taught my second class, which was very similar to my first. The biggest difference was the gender breakdown: 16 of the 20 students were girls, and they all sat together. When I asked why, they said it was because they lived in the same dormitory and were all friends. One of the male students had a different explanation: “Maybe they are afraid of us.’’

Everyone, especially the girls, spoke in a whisper that made it very hard for me to hear them. (I’ve been told that Chinese students are notoriously shy and reluctant to ask questions because they view the teacher as an authority figure.) I kept asking the students to speak up, but I finally gave up and stood right next to them.

Though I sometimes struggled to understand what they were saying, one thing was clear from my first day as a teacher in China: I am going to learn as much from my students as they learn from me.