Antarctica is a land of superlatives.

Not only is it the coldest continent on Earth, it’s also the driest, windiest and highest.

Given such extremes, it’s not surprising that the Frozen Continent has drawn explorers, adventurers, scientists and, more recently, tourists from all over the world to check out one of the last pristine places on the planet.

My wife and I recently joined that group during a 10-day cruise from Ushuaia, at the southern tip of Argentina, to the Antarctic Peninsula, the northernmost part of a continent that has been variously described as “otherworldly,’’ “mythic,’’ “rapturous’’ and “terrifying.’’

I’ve been fascinated with the place ever since high school, when I first read about Ernest Shackleton’s legendary Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-1917.

En route to attempt the first land crossing of the continent, the British explorer’s ship got stuck in pack ice and sank in the Weddell Sea just off the coast of Antarctica. After living in makeshift camps on a drifting ice floe for more than five months, Shackleton and his 27-man crew used three lifeboats salvaged from the wreck to reach Elephant Island, an uninhabited, desolate patch of land about 150 miles north of the Antarctic Peninsula.

From there, in a single rebuilt lifeboat caulked with seal blood, Shackleton and five crewmen set out on an 800-mile, 17-day voyage across the Southern Ocean to South Georgia Island. After landing, Shackleton and two other men trekked for 36 hours over glaciers and mountains to reach a whaling station where a rescue operation was launched. It took more than three months, but eventually Shackleton’s entire crew was rescued from Elephant Island without a single loss of life.

Needless to say, our Antarctic experience wasn’t so frightening or dangerous. But it was thrilling.

Just getting to Antarctica is quite an adventure.

We started out with a flight from Newark (via Houston) to Buenos Aires, where we spent an afternoon visiting a family we met 7 1/2 years ago in Patagonia. They live in Tigre, a prosperous waterfront town about an hour north of Buenos Aires where the father is the mayor and everyone seems to own a boat. We took a boat ride on a river lined with fancy dockside homes, ate at an upscale waterfront restaurant and walked through a pedestrian shopping area lined with arts and crafts stores.

The following morning, we flew from Buenos Aires to Ushuaia, a tourist town at the southern tip of Argentina where ships depart for Antarctica. There, we boarded Hurtigruten’s Fridtjof Nansen, named after a famous Norwegian explorer who led the first crossing of Greenland in 1888.

The ship, built in 2019, is a state-of-the-art vessel that uses hybrid power to cut fuel consumption. It has a capacity of 530 passengers, but only 443 were on board for our 10-day voyage. (Due to strict limits on the number of people who can go ashore at one time, ships that include landings can’t carry more than 500 passengers.)

The Nansen is categorized as an expedition ship, as opposed to a cruise ship. Expedition ships are smaller than their cruise counterparts, allowing them to visit hard-to-reach places in remote areas like Antarctica. They also emphasize education and adventure over entertainment and dining, which tend to be the focus on cruise ships. (Our ship even had a science center, complete with microscopes and other lab equipment.)

It took about 60 hours to reach our first stop, Winter Island, off the west coast of the peninsula. Most of the crossing was over the notorious Drake Passage, known as one of the most treacherous bodies of water in the world.

The sea was relatively calm on our first day, but the second day was a different story, with waves cresting at 17 feet and winds gusting at more than 60 miles per hour. The wind was so strong that whale and bird viewing sessions from the decks were canceled, and passengers wobbled around the ship like drunken sailors.

The reception desk was handing out sea-sickness pills and patches like Halloween candy, and I saw more than a few passengers grabbing barf bags that were conveniently located by each elevator. (Experienced crew members insisted that our passage was a relatively mild one. They recalled times when waves topped 30 feet and wind speeds reached 80 mph.)

When we weren’t eating, drinking or standing on the deck looking for whales, we spent most of our time during the crossing attending lectures on Antarctic wildlife, history, geography and weather presented by scientists, researchers and expedition leaders. Being an animal lover, I was particularly interested in the sessions on penguins, whales, seals and birds, which are the most common creatures in Antarctica.

Among the fun facts I learned: Killer whales are actually dolphins, penguins waddle because their legs and feet are awkwardly placed, and elephant seals can hold their breath underwater for two hours. (Lectures continued throughout the trip, on everything from glaciers and icebergs to rocks and wind.)

As we cruised along the peninsula, we left the ship for daily excursions on inflatable Zodiac boats. The first day, we landed on Winter Island to visit Wordie House, a former British meteorological station named after Shackleton’s chief scientist on the Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Built in 1947, expanded in 1951 and closed in 1954, it’s a small wooden shack that now serves as a reminder of a bygone era of polar exploration.

You can still see artifacts left behind when the Brits closed the place and moved to a bigger facility on neighboring Galindez Island: rusty coffee cans, cracked pots and pans, primitive bunk beds, clunky radio equipment and old-fashioned crampons. (In 1996, the Galindez Island complex was sold for one British pound to Ukraine, which currently operates a research station there.)

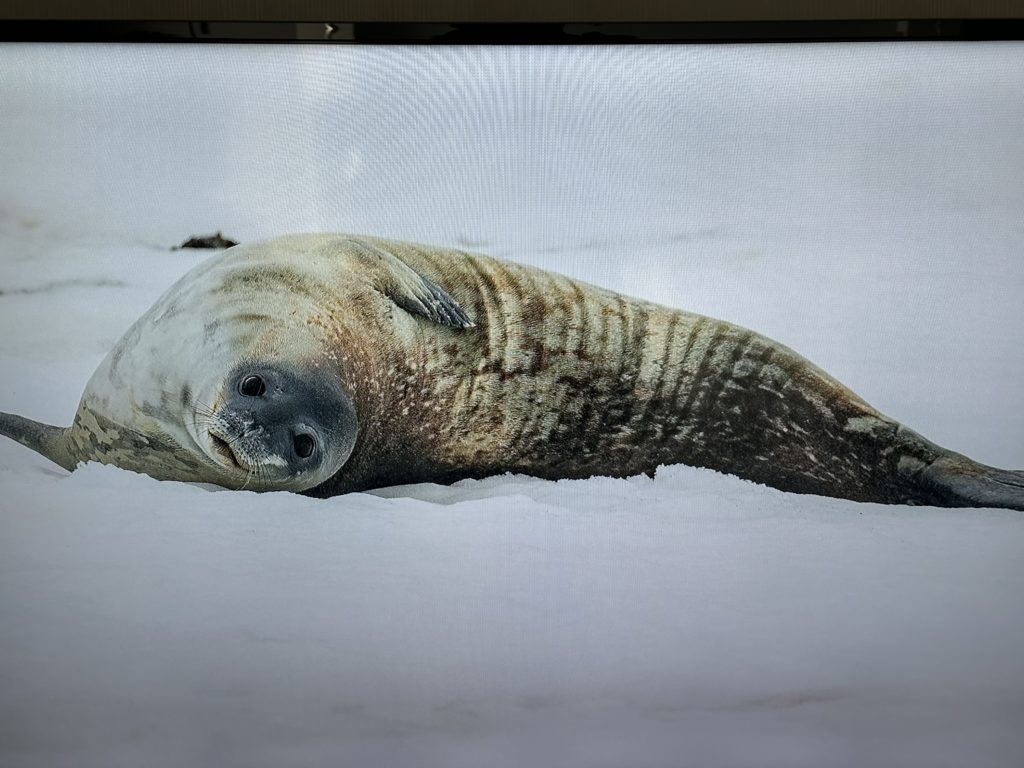

Using ski poles, we walked up an adjacent snow hill and got a great view of the surrounding rock formations and our black-red-and-white ship anchored in Grandidier Channel. We also spotted a Weddell seal lying contently on his side, oblivious to all the photo-snapping tourists about 30 feet away.

Later that afternoon, we took a Zodiac cruise around Winter and Galindez islands, where a large colony of gentoo penguins were perched on the rocks and swimming in the water, using their flippers to gracefully propel themselves above the surface. Gentoos are easily identified by the wraparound white band on their heads, which make them look like they’re wearing headphones. We also saw a couple of chinstrap penguins, distinguished by a thin black line that runs under their beaks.

That evening, starting at 9 p.m. in bright daylight (there’s about 20 hours of summer daylight on the peninsula), the ship passed through the scenic Lemaire Channel. Nicknamed “Kodak Gap’’ because it’s a favorite for tourist photos, the narrow channel is hemmed by steep, snow-covered cliffs and dotted with icebergs that sometimes prevent ships from passing through.

The Nansen moved very slowly through the channel to avoid icebergs and whales, which are sometimes maimed or killed by fast-moving ships. We saw a lot of whales on our trip (mostly humpbacks), usually visible by the white spray shooting up from their blowholes or their tails sticking out of the water. However, we never witnessed a whale breach, which is when it jumps out of the water and twists in the air like an acrobat before splashing with a thunderous thud.

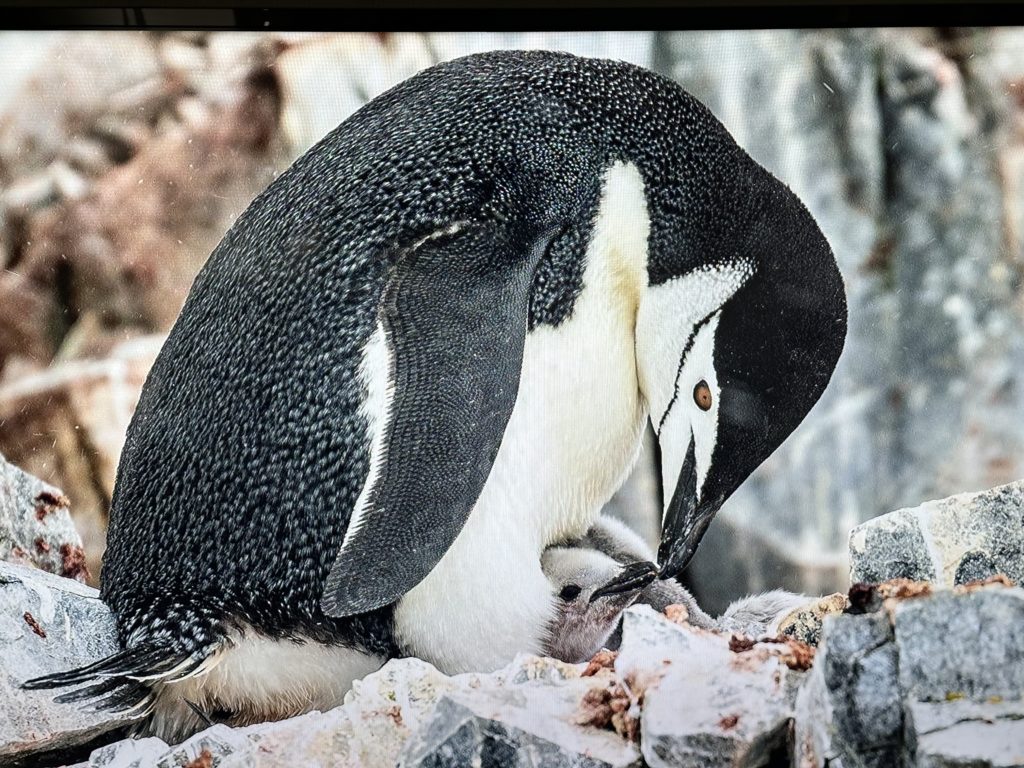

The following day, we cruised around Orne Harbour, where we saw colonies of chinstrap penguins and blue-eyed shags, birds with a blue ring around their eyes, pink feet and a yellowish nasal knob. Some of the female penguins had recently given birth, and our cruise photographer took a fabulous picture of a chinstrap tenderly feeding her chick. (Millions of penguins live in Antarctica, though no one is sure how many. The largest and best-known species, the emperor penguin, is rarely found on the peninsula and we never saw one.)

That day we also set foot on mainland Antarctica for the first time, making Pat and I official members of the seven-continent club. After our Zodiac landed on a rocky shore, we climbed up another snow hill where a chinstrap colony was hanging out at the top. Coming down the hill was quite precarious, even with ski poles, because it was easy to sink in patches of deep snow or slip on sheets of slippery ice.

COVID reared its ugly head on our third day in Antarctica (Friday the 13th, for you suspicious folks) when the ship’s captain announced that three cases had been discovered onboard. Up to that point, there was no mask requirement on the ship and Hurtigruten had just stopped mandating pre-boarding COVID tests. For the rest of our trip, everyone was supposed to wear a mask except during meals, though some passengers stubbornly refused. Fortunately, no one else got the virus.

En route to our next stop, we passed a small, inactive Chilean research station located in a place called Paradise Bay. If your idea of paradise is a bunch of wooden shacks in a freezing climate in the middle of nowhere, I guess you could call it paradise.

Our main activity for the day was a strenuous hike to Brown Station, an Argentine research base that was unoccupied at the time. (You can’t visit occupied research stations now because of COVID.) A colony of gentoo penguins makes their home at the station and their trail of reddish poop gave the area a pungent smell. Several penguins crossed right in front of us, waddling along a well-worn track known as a “penguin highway.’’

Brown is one of 70 or so permanent research stations in Antarctica that are operated by 29 countries. Most of them are only staffed in the Antarctic summer (October-March) but some operate year-round, even during the brutal winters when temperatures can plunge to minus-80 degrees at the South Pole and minus-20 in the coastal areas.

Since we came in the Antarctic summer and only visited the warmer peninsula, the weather was fairly comfortable when the wind wasn’t gusting. Most days temperatures were in the low to mid-30s, though it felt much colder when gale-force winds started blowing.

Global warming is having a major impact on the continent, melting glaciers at an alarming rate and forcing wildlife to adapt to a changing environment. While we saw plenty of large glaciers, we also looked at maps that showed how much smaller they’ve gotten in recent decades. When glaciers melt, they produce huge amounts of water that raise sea levels and threaten coastal cities around the world.

While several countries have made territorial claims in Antarctica, it isn’t owned by any nation. The continent is governed by the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, which designates it as an international refuge devoted to peace and science.

Our next landing site was at Damoy Point, the site of an old Argentine storage shed and a former British transfer station, where ships carrying personnel and supplies would stop en route to Rothera Research Station on Adelaide Island. Because sea ice prevented ship access to Rothera in early summer, those heading to the research station would fly there from Damoy Point on a small plane that would take off from a 1,300-foot “ski-way.’’

Like Wordie House, Damoy Hut is still stocked with can goods, snow shoes, books, bunk beds and scientific equipment left behind when the British stopped using the building in 1993.

We also saw several colonies of gentoo penguins, who were having loud, animated conversations. The high-pitched sounds that penguins make are usually described as squawking, braying or honking. Their individual calls, or vocalizations, allow mates to recognize each other and their chicks, which is necessary because it’s difficult for them to recognize each other by sight.

Penguins are the best-known birds in Antarctica, but there are dozens of other avian species in the region, including skuas, albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters, sheathbills and terns. We saw a lot of them on our trip, but the most striking were the wandering albatrosses, which have the longest wingspan of any bird. (Our expedition groups were named after bird species and ours was the black-browed albatross.)

Antarctic cruises often have to change their itineraries and activities on the fly because of fickle weather. We were fortunate during our trip, with only one sleet storm, a few light snowfalls and occasional gusts of dangerous winds. One camping outing and a couple of kayak ventures were canceled due to bad weather, but all our landings took place on schedule until the seventh day, when fierce winds prevented us from going ashore at Whalers Bay on Deception Island, the site of an old Norwegian whaling station which contains a cemetery with 35 graves and a monument to 10 men lost at sea.

Fortunately, we were able to make landing at a different site called Half Moon Bay, where we walked on a snowless, rocky shore and saw colonies of chinstrap and gentoo penguins. We also noticed a cluster of red buildings, which turned out be an empty Argentine research station.

But the highlight there was my polar plunge into the freezing waters of the Antarctic.

After stripping down to a bathing suit onshore, I quickly walked about 25 feet into the bay and dove into the frigid water, which was 39 degrees Fahrenheit. My whole body went temporarily numb, but it actually wasn’t as bad as I anticipated. I only stayed in the water for about 15 seconds, and the worst part was getting dressed back on the shore.

The expedition leaders had laid out a rubber mat where polar plungers could leave their clothes and boots before going in the water. Back on land, after toweling off, a lot of us struggled to put our clothes back on over our wet bathing suits while we shivered in the cold. But we all managed to get dressed, get back on our inflatable boats and return safely to the ship.

That was our final landing of the voyage. The ship then headed back across the Drake Passage to Ushuaia. The return trip was a bumpy one, but by then most passengers were used to the rocking motion and I didn’t see nearly as many vomit bags.

Along with viewing the spectacular scenery and wildlife, we got to meet people from all over the world on the ship. The crew of 153 represented 26 nationalities, and the passengers came from 20 different countries: the U.K., Germany, France, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, Norway, Argentina, Uruguay, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Japan, Canada and the U.S. All the lectures and announcements were made in English and German, but you could hear passengers speaking more than a dozen languages.

At the start of the cruise, our expedition leader told us there were three ways to describe a day in Antarctica: good, better and amazing. As it turned out, every day was amazing.

Hi Rick. Marsha and I really enjoyed your Antarctica post. Thanks for sharing!

This is fantastic, Rick! Great descriptions, history, pictures and videos!

Rick, I so very much enjoyed the pictures and your glorious description of the trip. And just as much, I liked seeing Antarctica this way . . . . From the warmth of my home and the stillness of terra firma. Thank you for sharing such a super adventure! Congratulation on the polar plunge too. Someday I’ll tell you about mine after every marathon. Diana

Hi Rick,

Thanks for sharing your ever-entertaining travelogue of your adventures with Pat to Antarctica! Fascinating reading! I always learn so much from what you write!

Interestingly, my sister’s niece and husband, Peggy and Dick who live in Michigan just returned yesterday from this same trip! They drove to Dallas and flew from there to Buenos Aires, before cruising to Antarctica. While they were gone, my sister, Cathie, and her husband, Ron, took care of Peggy and Dick”s three dogs. Cathie and Ron also have three dogs, so they had quite a canine crew for 18 days.

Now Peggy and Dick will stay for a week-long visit before Cathie and Ron leave to attend their grandson’s graduation from Marine boot camp at Fort Pendleton, CA. Peggy and Dick will care for all 6 dogs at my sister’s house while Cathie and Ron are away. Just the coordinating of all that travel, to and from with 6 dogs makes my head spin! My sister and her husband are both in their 80s. Remarkable!

I am going to forward your blog to my sister so she can share it with Peggy and Dick. It seems to me that you came very close to traveling together!

Be well!

Love to you and Pat,

Marie and Ray

BTW Rick, we ladies all enjoyed your Polar Plunge picture. You would be competition to most 50 year olds. However you are staying so fit is amazing. Good for you. Keep it up as I’m sure Pat is appreciative. Smile.

Hi Rick,

I always love your travel journals!!! I only wish they were longer. I don’t want them to end. You and Pat are the cutest couple next to all the glaciers, sea ice and penguins!!! Congrats on your polar plunge!! Wow. Very impressive.

I can’t wait for your next trip.

Elissa

Hi Rick! What a feather in your cap- a teal polar plunge!! I too am a Shackleton admirer and your descriptions reminded me much of his stories. Glad your 10 day expedition had you safely back in Tiero del Fuego. And now back home What an adventure!

Susan

Hi Rick! What a feather in your cap- a real polar plunge!! I too am a Shackleton admirer and your descriptions reminded me much of his stories. Glad your 10 day expedition had you safely back in Tiero del Fuego. And now back home What an adventure!

Susan